I’d like to think that the level-setting standard of “not enacting unnecessary cruelty” that was first established when our forbearers began our movement reaches now across our country; That we have achieved that base level of decency, at least for companion animals, at least within the walls of the companion animal protection movement itself, that was sought after in the 1870s.

Everyone has bad days. Today I am not sure this standard is true. I don’t want to be specific, but I’m definitely feeling angry and a little sad today.

There are still areas across the country where the primary challenge (in shelters!) is ensuring that the most basic of compassion and care occurs for the companion animals we are entrusted to care for.

There is also a continuing shadow of hatred directed at any industry watchdog who dares to suggest that killing pets without applying lifesaving efforts or acknowledging the possibilities of progress is not an act of kindness. That killing animals unnecessarily not because of lack of resources, but because of lack of effort, is acceptable and not a cruelty. Our field often chooses to protect their own regardless of their demonstrations of their ethics.

If the animal welfare movement is an evolution that began with the socially acceptable act of clubbing street dogs to death in front of children in broad daylight, I truly hope it ends with a communal understanding that every animal has an intrinsic and individual spirit and value. Sadly, there are days like today when I feel like we all are not ready to receive this view.

I know that is why I am here, working toward it. Just like George Angell and Caroline Earl White and Henry Bergh, what we in the field are doing today is level-setting. We are raising the bar to that place where every animal is recognized as an individual with value.

And now that I’ve told you about my bad day – This blog post was supposed to be about Caroline Earle White’s personal beliefs and how they influenced our industry, and so it shall be. She was one of the people that we can look back on when our work feels impossible, and so today I’m looking to her for her strength. Not a one of my bad days will be akin to hers, when fighting for animals meant fighting for more humane methods to kill them.

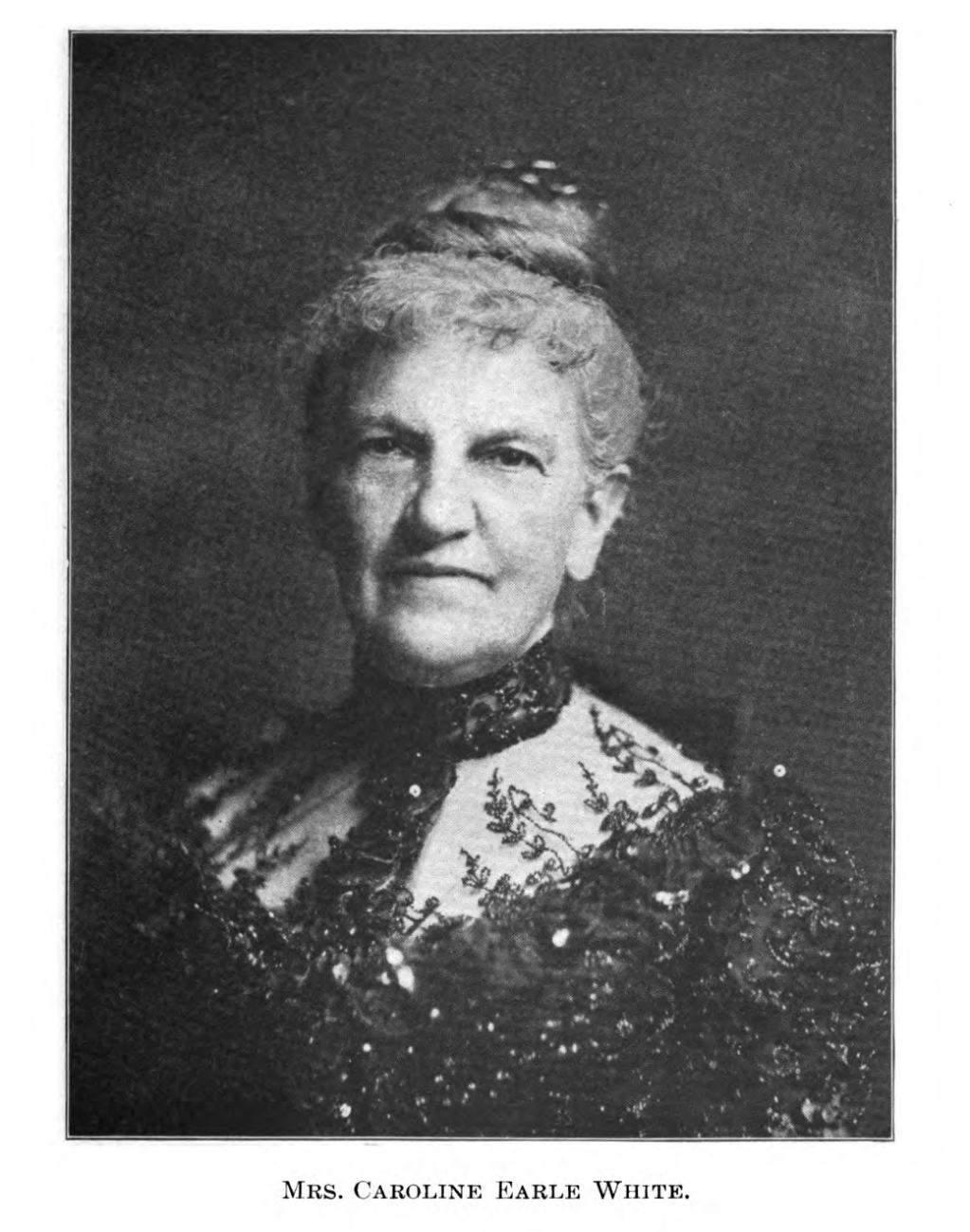

Caroline Earle White, the founder of the Philadelphia roots of the animal welfare movement, establisher of the Pennsylvania SPCA, Woman’s Animal Shelter, and the American Anti-Vivisection Society, was born in 1833 into a wealthy Unitarian Quaker household. Her father was a lawyer and because of his wealth, Caroline was able to receive a first class education that became essential later when conducting work within the movement. She was known as a lively personality who exuded not only compassion and a great love for companion animals but also intelligence and a sharp wit.

At the age of 17, she met and then later married attorney Richard P. White, a devout Catholic. Caroline had experience with the Catholic faith as a child, as she and her siblings liked to visit the Catholic church occasionally and see their masses. Her family was not at all opposed to the Catholic faith and although they subscribed as a family to Quaker beliefs, there was no animosity toward Catholicism, as others may have experienced in that time.

That being said, Quakers fundamentally take an individualistic approach to religion, believing that each person has their own “divine and internal light” that drives their relationship with God. There is no clergy and only a loose affiliation to scripture. You are guided by the internal morals you are supposed to have been born with.

Catholicism takes a highly hierarchal approach, believing that the word of God requires translation and interpretation, most often through a priest and in the form of a Sunday sermon. There is black and white, and very little in between.

Caroline experienced both religions as a devotee, converting to Catholicism two years after her marriage, following the experience of a trip to Ireland with her husband and the introduction and ability to confer deeply and often with a priest named Father O’Brien. You can read about her conversion in her own words here.

Being Catholic became extremely important later in life to Caroline, and she dedicated a large portion of her time to religious work, serving in multiple religious organizations.

In addition to this religious upbringing, she was also greatly influenced by her family’s deep abolitionist involvement. Her father once ran for Vice-President on the Liberty Party ticket, and her Mother’s cousin was the famed abolitionist speaker Lucretia Mott. Caroline gave up her Christmas money for the anti-slavery movement more than once.

She also had a deep, early, and profound love for animals. When she read about the work Henry Bergh was doing in New York, she was quick to reach out in order to begin her own chapters of anti-cruelty societies in Philadelphia, with his advice.

Caroline’s moral influences had a profound impact on the ways she conducted her work. One of the ways we can “Hear” from her most directly is in her role as editor of The Journal of Zoophily, the newsletter of the Anti-Vivisectionist Society.

Caroline often referenced her upbringing and a great curiosity for the Catholic faith as something that contributed greatly to her desire to communicate logically. Much of her contribution to the movement was in the way she chose to communicate out what she saw. She spoke the truth of what was happening without couching it, but she also worked to make it relatable to all, and used logic to make her points.

Religious parallels and parables often show in her pieces, such as this piece about man’s intrinsic nature to be cruel.

Here, on circus animals:

And in 1886, when vivisectionist William Keene published his first work in defense of vivisection (Our Recent Debts to Vivisection) following his commencement speech on the same topic at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, Caroline was quick to reply with her own well thought out reply, appealing to the graduates as a woman herself, and with kindness and logic.

While George Angell’s approach was that people must be educated to then know to be kind, Caroline Earle White’s proclivity to appeal to the goodness she believed people to possess is hallmark of her approach to furthering the movement. Caroline Earle White believed that you only had to put the facts in front of people and they would both understand the urgency and carry the message forward. Her bravery was necessary, if not always popular. When faced with those questioning her help for pets when there was so much need among men, she was quoted:

“But are we not working for human beings? Are we not constantly striving to make men and woman more humane and disposed to all kindly feelings and to teach children to become gentle and merciful? Is not everything which tends to elevate man in the mortal scale a benefit to him?”

Caroline Earle White’s impact to our movement extends far beyond her role in advocating for humane treatment of animals. She helped lay a foundation that continues to inspire others today when the movement is so difficult still. Her legacy encourages each of us to reflect on and refine our daily practices so that we, too, can move us forward.

-Audrey

One response to ““That of God in Every Man.””

Thank you Audrey, By illuminating the history of animal welfare you help us all to see our roots and the strong lineage of kindness that is the foundation of our movement. It’s fascinating how tensions between “intellect” and “feelings”, “head” and “heart” even “male” and “female” played out back then as they do now!

Keep up the good work,

Cyrus

Cyrus Mejía

Co Founder, Board Member

Best Friends Animal Society

5001 Angel Canyon Rd

Kanab, UT 84741

Cell 435-899-1756

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike