Hello, friends. I hope you are not working too hard this week as routines are re-established and our post-holiday cadence establishes itself. I myself have only used circle back in a sentence once this week, and for that I am proud.

Recently, a new friend expressed to me their desire to better understand how we got from the early movement to the later spay and neuter push; what activity fell in between, and how did that activity further influence our current policies? Those of us working within the humane movement tend to be told the (a?) story of Henry Bergh like it’s a fairy tale, but then not much else. Even if you make a concerted effort to learn our history, you really have to dig for this time period.

In my perspective, between 1920 and 1960, the humane movement largely focused itself around rallying public support (and financial support) for their work, deciding what issues were in fact “our” issues, and, importantly, around preventing and then eradicating rabies. This is an interesting juncture of activities, because particularly as we near the later part of this era, we also see a decline in the transparency around shelter death. As such, recommendations around rabies control, which were deeply rooted in “every stray belong in the shelter” greatly influenced later intake contracts and policies.

An interesting snapshot of this time period can be found by looking at a book called “Rabies.” It was written in 1942 by a gentleman named Leslie Tillotson Webster. Webster was a physician and researcher who worked in epidemiology and bacteriology at the Rockefeller institute of Medical Research from 1920-1943, when he passed away. His main field of study was the importance of natural resistance to disease.

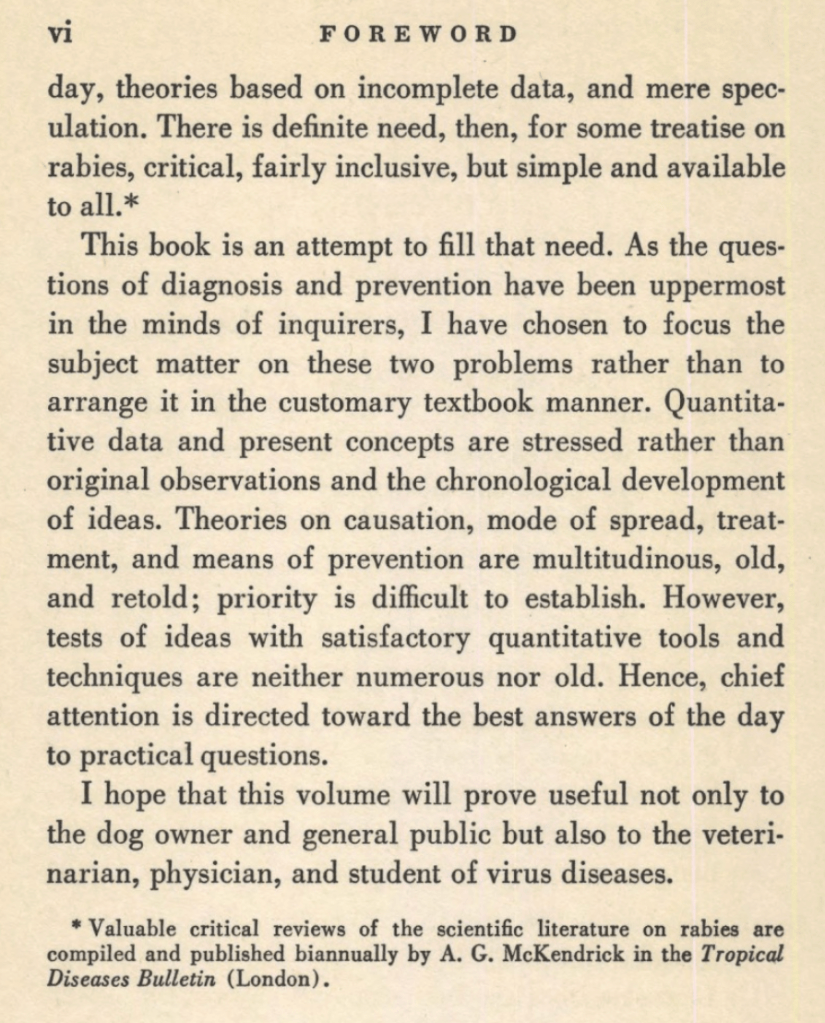

He introduces his book with the forward below, identifying his intention to create a modern treatise on rabies that is simple, available to all, and can serve as a resource for any interested party. This book became a resource to government officials seeking to control rabies, and by translation, strays, in their communities. Webster likely had very little familiarity with animal control realities, but his work influenced intake policies, quarantine laws, and the process that hundreds of thousands of shelter pets were impacted by.

We tend to think that by 1942 we were in a place where vaccination of all dogs was probably coming to be mandated, but in reality, in 1942, some people were still debating whether or not rabies was real. Indeed, an early section of the book, entitled “The Diagnosis of Rabies” unpacks which hosts can carry the disease, how it is caused, and even contains a section called “Is Rabies a Myth?” intended to prove out that rabies is, in fact, real, by comparing the progression of rabies to other infectious diseases. Once he’s established that the virus is in fact real, Webster looks at the modes of transmission of the virus by looking at decades of animal testing.

One of the questions that I certainly had when studying this time period is why the vaccine, which was at this point very much widely accepted to be preventative in humans, was not also accepted to be preventative in dogs and recommended for mass vaccination. This is a little bit complicated but I’m going to do my best to unpack it as a layperson. There are a few reasons.

Trigger warning here: animal testing descriptions, so skip this next section if that’s not something you’d want to read.

There are two types of rabies virus in relationship to studies. The first type, “street” virus, is pretty self explanatory; it’s the virus from a rabid animal in the streets. The second type, “fixed” virus, is a little more complicated. When Louis Pasteur was developing the Pasteur treatment in France in the 1890s, he used first dogs and then rabbits for his experiments. In order to standardize the incubation time, he passed the virus from a series of animals, one to the next, for nine iterations by injecting it into their brains. So the first rabbit became rabid, he took that virus and caused the next rabbit to become rabid, etc. and onward until 9 iterations had been repeated. What this accomplished was a rabies virus that induced rabies in a uniform seven day. This stronger and consistent version of virus was what was used universally in testing, injected directly into the brains of animals to induce rabies. Most of the animal testing experiments of studies following this used this “fixed” virus injected directly into the brains of animals to determine what the minimum doses were required to induce rabies. But there are differences between “street” rabies and “fixed” rabies, and the way that those viruses show up in the tests. Most of the experiments that had historically been conducted around the prevention of rabies (and there were very few) with a pre-exposure vaccine had been conducted with fixed virus.

Another consideration was that by this time there were so many types of rabies vaccines for humans that it was difficult to test the efficacy of all of them on dogs. The ways that the virus was diluted (to prevent actual infection) varied from type to type, with some more effective than others. All of the vaccines were what we would consider to be killed virus, and in a very small but not insignificant amount of instances, the “killed” piece of these vaccines had been found to fail and to actually induce rabies in people.

Many of the studies also involved small samplings of animals, animals other than dogs, and focused around curative measures and of course, treatment and prevention in people.

At this time, there were simply considered to be a lack of studies that accurately encompassed dogs, in sufficient quantity, with “street” virus exposure that proved conclusively that any of the preventative vaccines worked consistently enough to prevent rabies. Webster recommends that although research is promising, there isn’t one vaccine studied well enough to be pronounced effective enough to recommend mass vaccination of dogs.

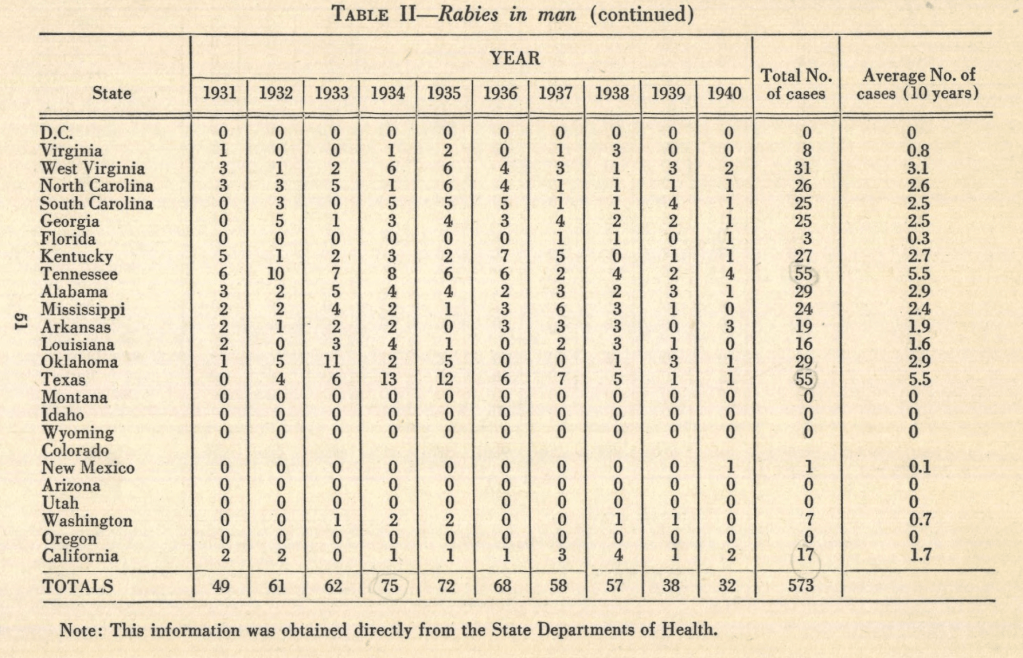

Interestingly, a table is also included that illustrates just how few cases of rabies in humans remain in the United States at this time. While the table doesn’t illustrate the reduction from past decades (which is significant) what it does do, if you’re in the know, is essentially prove out that the current dog control methods of catch/kill of strays are effectively reducing the cases of rabies in people.

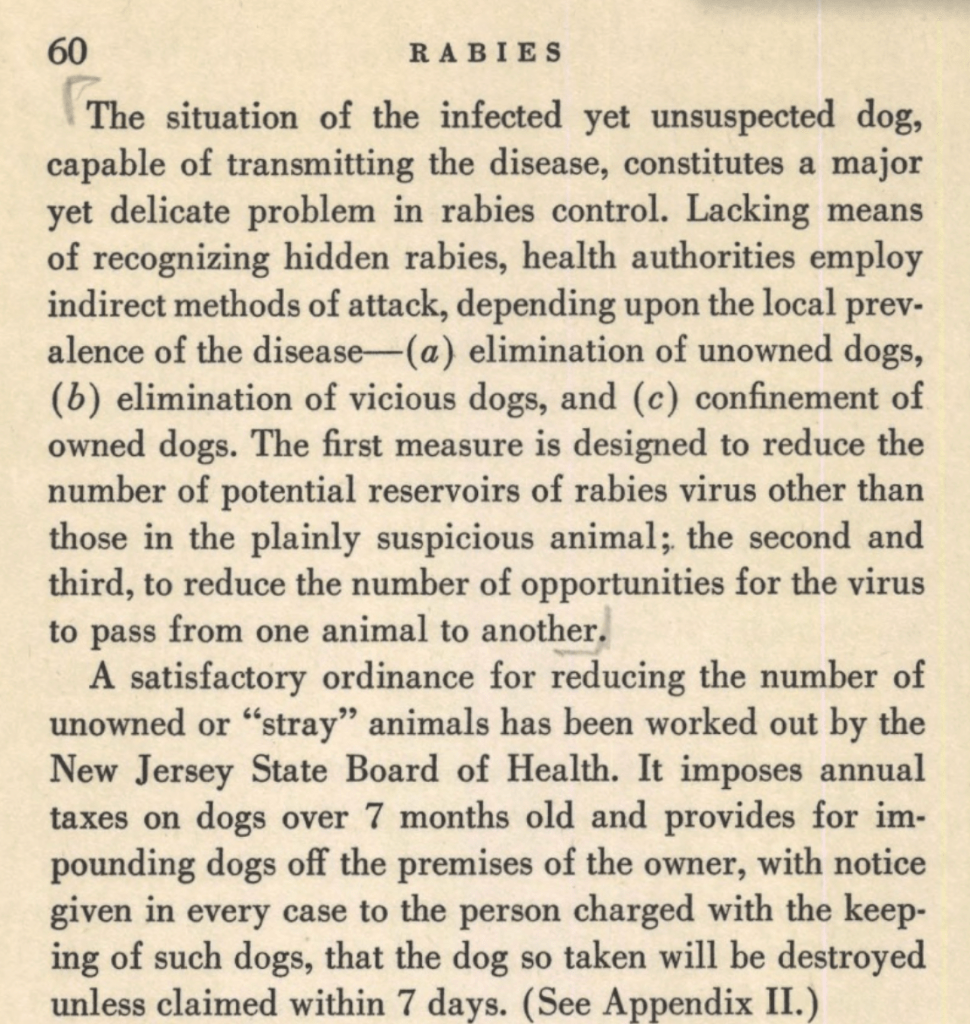

Of course, what we’re left with is a scientific community that in 1942 was still recommending catch/kill for stray dogs. So what were those specific recommendations? Webster’s chapter on rabies prevention takes care to outline individual responsibility as well as governmental responsibility, highlighting the importance of a “united understanding for control of rabies infection plus a support of official recommendations.” That’s a big ask for any public, if you ask me. In essence, though, he touts reducing the opportunity for infection to pass host to host by reducing the reservoir of virus, as well as building up the resistance in the community. He aligns rabies to other various diseases, and then aligns the most common reservoir of rabies disease in communities with the stray dog.

There’s also this chart which illustrates transmission and reservoir of other diseases, which, for some reason, I find hilarious. I think it’s the kid with the bat.

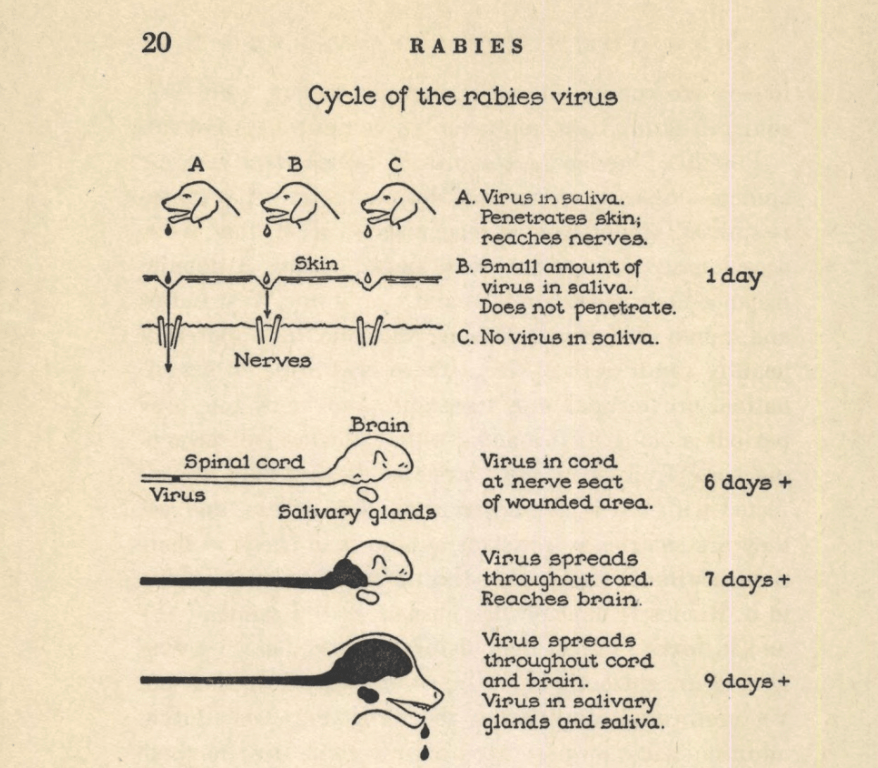

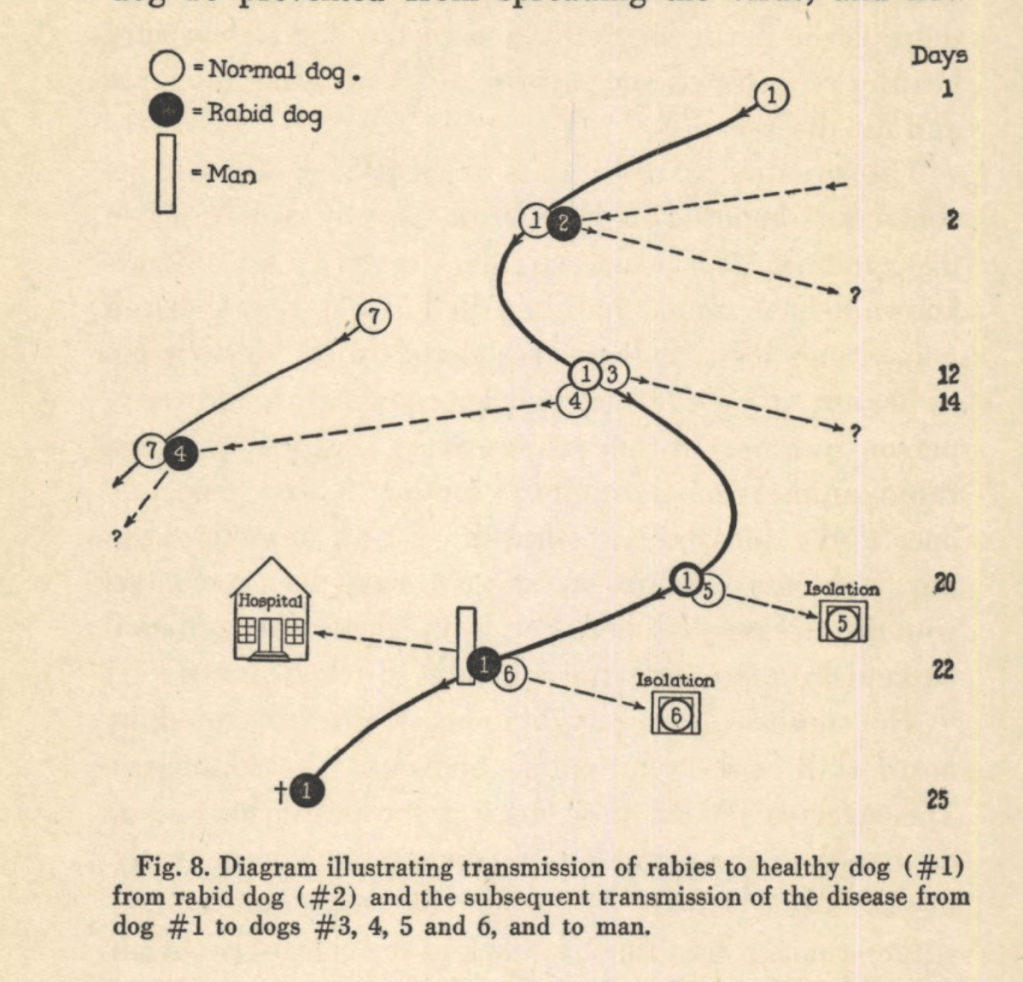

Anyway…He goes on to say that in order to reduce the load of rabies in the community, the only logical option is to reduce the stray dog population. Here’s another chart about how dogs transmit the virus that is not, in my opinion, very good at all.

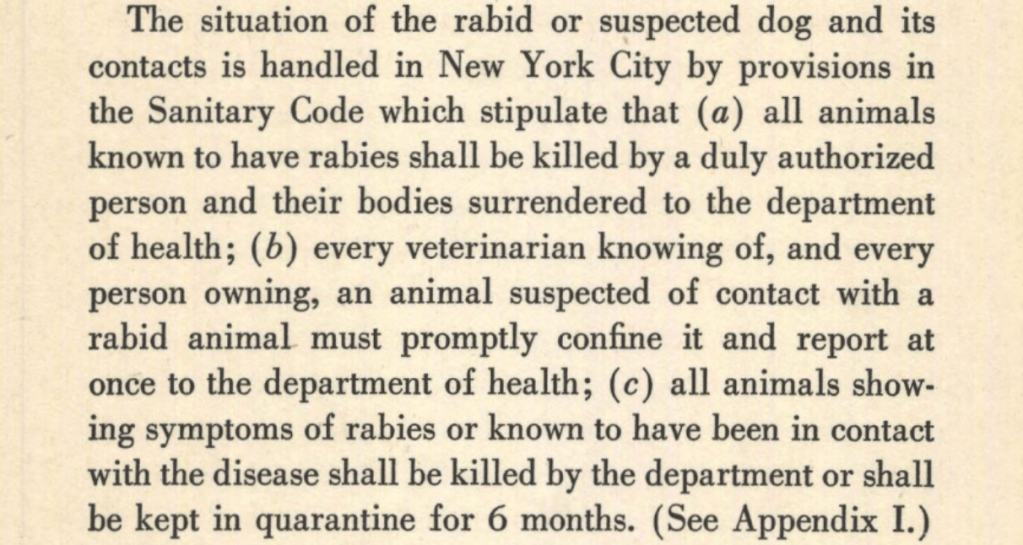

From here, Webster does describe that the situation can be delicate if involving an owned dog and details quarantine procedures recommended for exposure and the importance of reliance on veterinarians for their expertise. He references back to a New York City ordinance that points to the appropriate management of known to be rabid animals.

And finally, the recommendation that has affected shelter pets – the recommended removal of stray dogs from communities due to their potential to harbor disease.

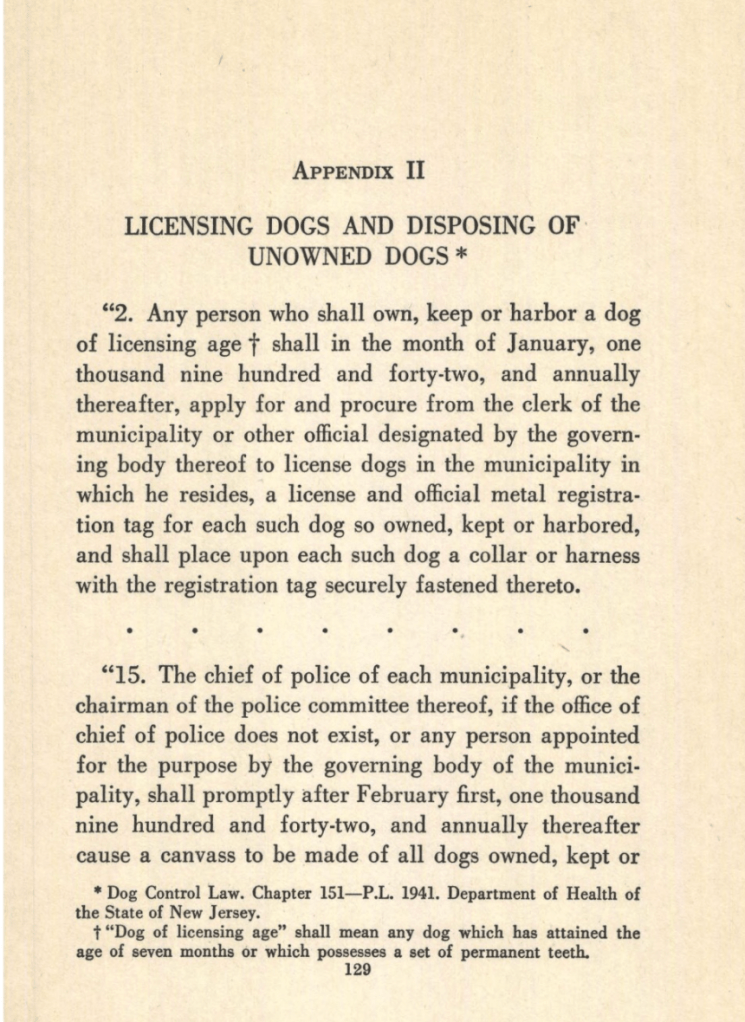

This recommendation points back to a New Jersey ordinance that had been in place for some time (although I could not find the original date of implementation) recommending the removal of all unowned dogs and a regular sweep to confiscate any dog without a license. Again, I think it’s very important to point out here that licensing in this time was simply to prove ownership – there was no vaccine requirement. The goal of the license was to prevent free roaming dogs.

These New Jersey ordinances are provided in the appendix of the book, ready for any official to copy paste into their local code.

Soon after the publication of this book, science caught up and by 1950, for the most part, prophylactic vaccination of dogs became recommended, if not yet required by law, ushering in what I like to think of as the era of public responsibility to pet ownership in the humane movement. I’ll look at that another time, and with that, my friends, I’ll leave you. If you do decide to read this book, I’d love to know your thoughts.

-Audrey