Trigger warning: The content included here is not particularly uplifting to look at and depicts images of dead pets, and pets being caged, abused, and killed. All images were at one point intended for public consumption. Please consider your mental health.

When Henry Bergh asked Henry Carter (better known as Frank Leslie, of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News) to design the seal of the A.S.P.C.A. in 1866, I’m not sure he ever imagined that his vision of a mighty angel raising a sword to defend against cruelty would eventually be translated to Sarah McLachlin asking for 60 cents a day to help sad looking pets in cages. (Many of them with one eye, for some reason.) However, if he DID know, he actually might have been into it.

You see, Henry Bergh was what we would call “enforcement minded” today. He truly believed that in order to change the societal view of how we treated animals, we needed to center their suffering in clear view and that punishment was the best option to correct any offense. The original, tiny office of the A.S.P.C.A. was filled with pictures and instruments of torture; everything from elephant hooks used to move circus animals to photos of bloody pigeons from pigeon shoots. He displayed a taxidermy dog from a dog fight, injuries and all, at the 1876 centennial exposition. The early ASPCA publications told some incredibly horrific tales under his early purview. He talked of the horrific suffering of animals in great detail, whenever he could, however he could. It might have been necessary, and it certainly set the stage. It’s important to remember that this point of view had very little precedent. In the eyes of society, which had been heavily influenced by religion, many believed that animals could not feel pain or emotions. The bible itself said that God had given man dominion over the animals.

Henry Bergh prioritized giving examples of cruelty and how cruelty corrupted society. This was a concept he called “Cruelism.” It was this shock-and-horror communication that Henry Bergh brought forth that helped the very early days of the A.S.P.C.A. gain the media coverage that it did, and ultimately become successful. In true Victorian fascination, the papers loved printing anything shocking. And shocking this content was, even though most people had been living alongside this type of cruelty for years, accepting it as normal. The idea that witnessing it might make a husband beat his wife or child was new.

The idea of centering the suffering of animals was taken up early on by others in the movement. Caroline Earle White, of Women’s P.S.C.P.A. and P.S.P.C.A. respectively, and then later the American Anti-Vivisection Society, also shared this view and the periodical of that organization, the Journal of Zoophily, may contain some of the best examples known.

Other early leaders, such as George Angell of the M.S.P.C.A., leaned more toward education, preferring to change hearts and minds with first person tales of animals acting heroically and leaflets describing how animals could feel emotions and pain, similar to humans.

Because of the way that the humane movement spread from city to city, with representatives from the A.S.P.C.A. and other, larger humane organizations visiting new places and starting chapters as calls for help arose, in each new location, the methodologies that were used for communicating to the public were also carried from place to place. This is why we often see periodicals with this type of story telling immediately spring up soon after new orgs are founded.

While it’s true that the iconic 2007 commercial is probably the most well known example of Sadvertisting, it’s interesting to look at other examples that have shaped the movement as we know it today.

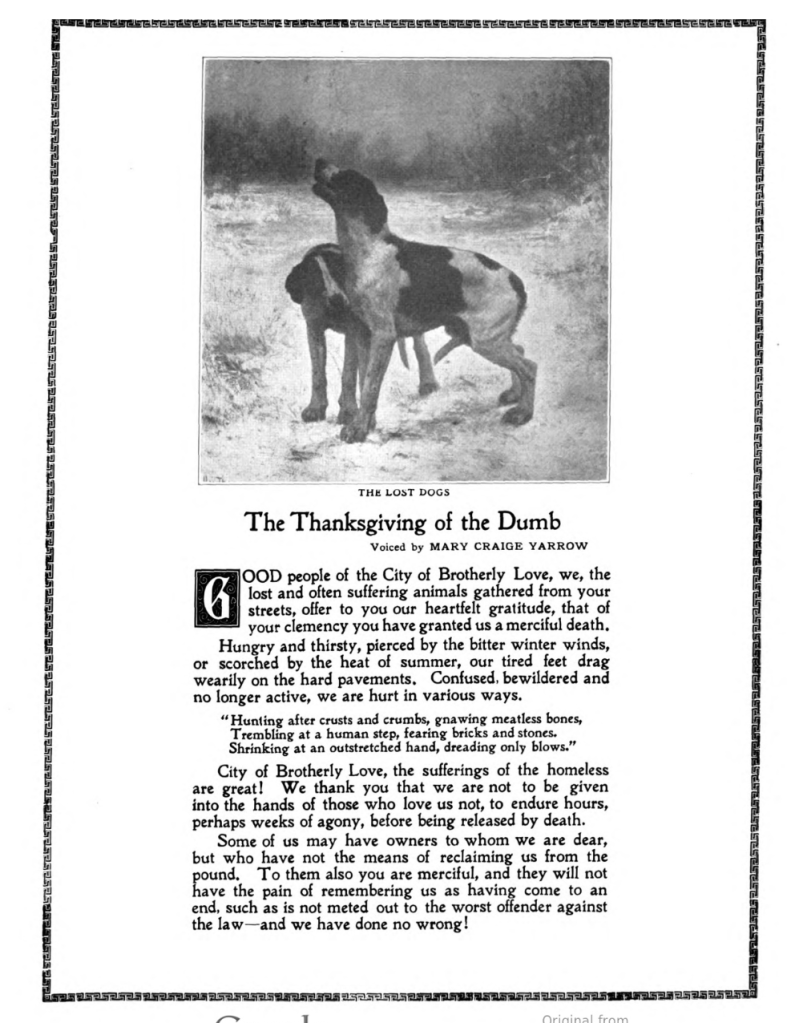

Sadvertising is a way we can see shifts in the way shelters see their role. One of the first big shifts is from the original, singular idea and intention that stray pets entering the shelters were the result of a public safety and nuisance issue to the idea that pets entering the shelters were better off being killed than being on their own. Their deaths were portrayed as mercy, with the messaging that they were of low value and would experience a life of cruelty and torture on the streets.

We see this particularly in times of economic hardship, such as during the great depression and during world war 2. Ads that encouraged people not to abandon their animals became normal, if not abundant.

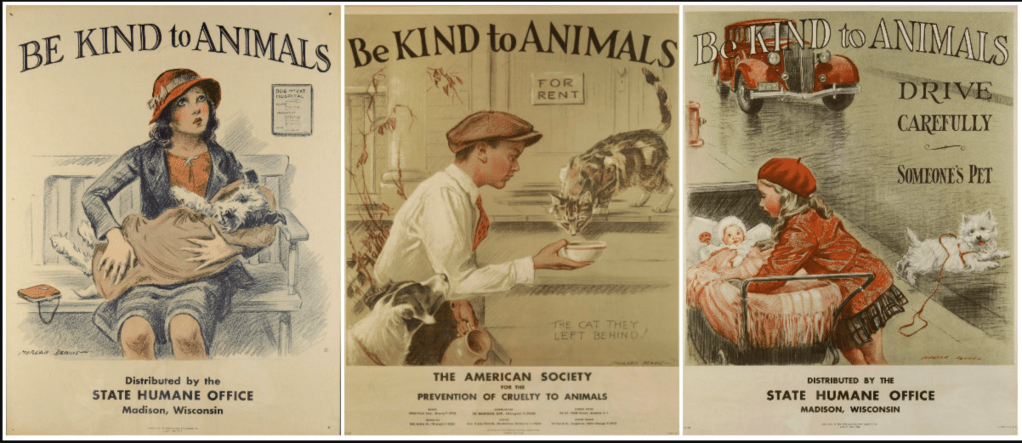

It’s interesting that during the time of about 1925 up through the 1970s, most talk of killing pets in shelters was eerily quiet. The movement had established that shelters were where pets went to die, and it was the public’s moral responsibility to bring them there. It had become normalized, and was very rarely mentioned even in the periodicals of the organizations themselves. Instead these publications and others shifted to individual animal stories, and stories related to specific cruelties like trapping, the perils of circus animals, tail docking and horse blanketing. Advertisements from this period were generally of a cheery, generic “Be kind to animals” tilt. This is the time period where a lack of transparency about what happened to pets in shelters truly took hold.

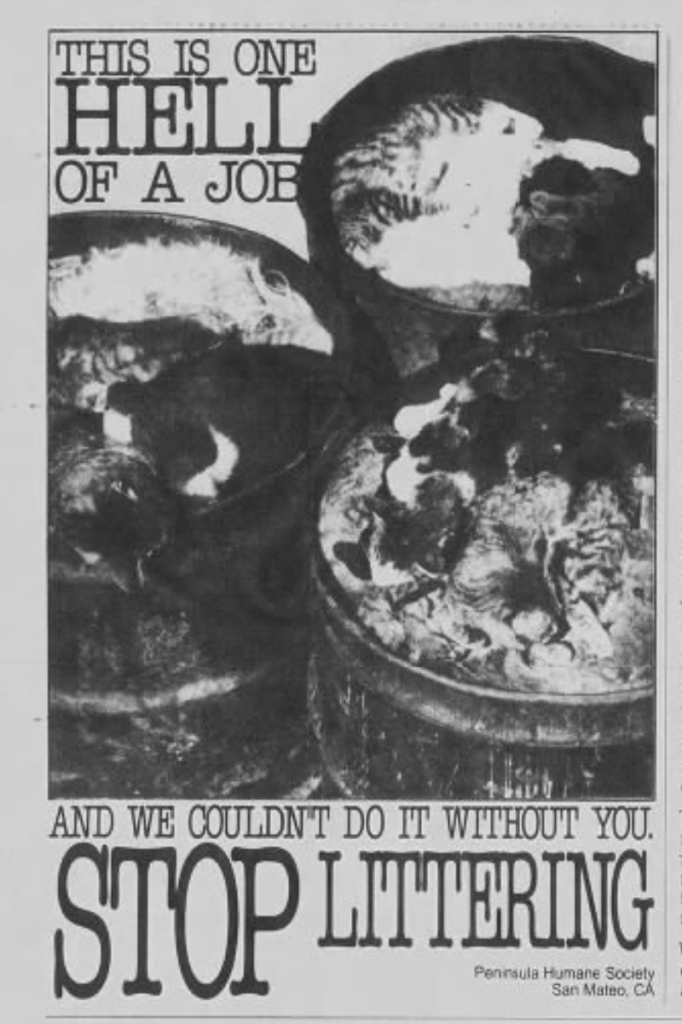

Yet, by the late 1970s, Sadvertising showed up again. Now, the ads had shifted to the idea of public responsibility. This type of ad really peaked in the 1980s and 1990s. As spay and neuter became available and spay and neuter campaigns took off across the country, pet overpopulation was often portrayed as the result of an irresponsible public. Images based on shock value began to appear, often including dead animals or threatening messages.

Today we still struggle to advocate for pets while portraying them with dignity and value, but we’re learning to do better. The biggest negative effect of sadvertising has been that people don’t want to visit shelters because they are afraid of what they might see when they get there. In fact, it’s one of the main reasons people choose not to adopt. If you doubt this, think of every time you’ve ever told someone you work in an animal shelter. The reaction is often “I could never do that!” That gives a good depiction of what people think they will see when they visit.

While many organizations still rely on the shock value of individual cruelty stories to raise money for specific pets in their care, it’s important that we tell these difficult stories in a way where pets are uplifted and valued. We are fighting many, many stigmas on behalf of these animals, but we also are their biggest cheerleaders.

I’ll reiterate that 100 years from now, someone hopefully will be writing something like Barking at the Knot, covering this part of the humane movement. The choices we make now are the ones that will be reflected there.

It’s possible to advocate and still illustrate how wonderful animals are. I’ll close this piece with a great example of that from Best Friends Animal Society, where I am blessed to work.

I hope you all have a wonderful week. Comments appreciated!

-Audrey

One response to “In the Arms of the Angel: The Strange History of Sadvertising”

[…] recently covered the concept of “sadvertisting” and how as the availability of spay and neuter increased, it led to a culture of shelters […]

LikeLike