It is the nature of the human race to rally for the cause when we feel an injustice is being done; the whole of the humane movement is based on that concept. Advocacy is powerful and it is necessary. That being said, we all know that advocacy and animal welfare have a history that provokes some strong feelings. I think this is mostly because our society has never been very good at agreeing on what “should” happen to animals. Standardization and transparency have never been shining pillars of the governance of animal shelters or of the humane movement. When advocacy gets uncivil, things can get very, very ugly. While we tend to think of angry advocates as a modern problem rooted in the evils of social media, they were as active in the 19th century as they are today. Muckraking was a style of investigative journalism that focused on exposing injustices. We tend to associate it more with things like Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” than we do with the A.S.P.C.A., but muckrakers ran with the story below, and if you think facebook is bad, well…hold on to your derby.

No story I’ve found about angry advocates is more relatable (or more fascinating) then that of the group of individuals who called themselves The Henry Bergh Humane Society, and the events that occurred between 1904 and 1907 around their dissatisfaction with the A.S.P.C.A. – or the S.P.C.A., as they referred to it. They intentionally dropped “American.” That’s how petty it got.

I want to warn you ahead of time that this is a LONG story. I’m going to have to tell it in parts and in truth, I debated telling it at all because it’s perhaps better suited for long form content. That being said, there’s not a line of people ready to tell this tale, I don’t have time to write a novel, and I think it’s important one…so here goes.

In April, 1904, in the Daily Local News, the headline reads “New Society to Rival the S.P.C.A.” and the article invites readers to attend a meeting organized “for the purpose of discussing the formation of a new organization.”

Dissatisfaction had been quietly brewing behind the scenes for some time around the effectiveness of the A.S.P.C.A., and like all stories like this, there were many contributing factors.

The first was the sheer size of New York City relative to the scope of work the A.S.P.C.A. was expected to conduct. As the city expanded, the population boomed and from 1890 to 1900, it had more than doubled in size to over three million people. As you can imagine, with the people came the animals, and there was more work to do than ever before. You’ll remember that much of the work of transporting goods and people was still done by horse in city streets. This was just before the regular availability of rabies vaccines (although the cure had been discovered) and at the height of panic around dog days. Complaints about stray cats littered the newspapers, and livestock was still moving crosswise through the city during certain hours of the day, meaning escaped cows were still a problem.

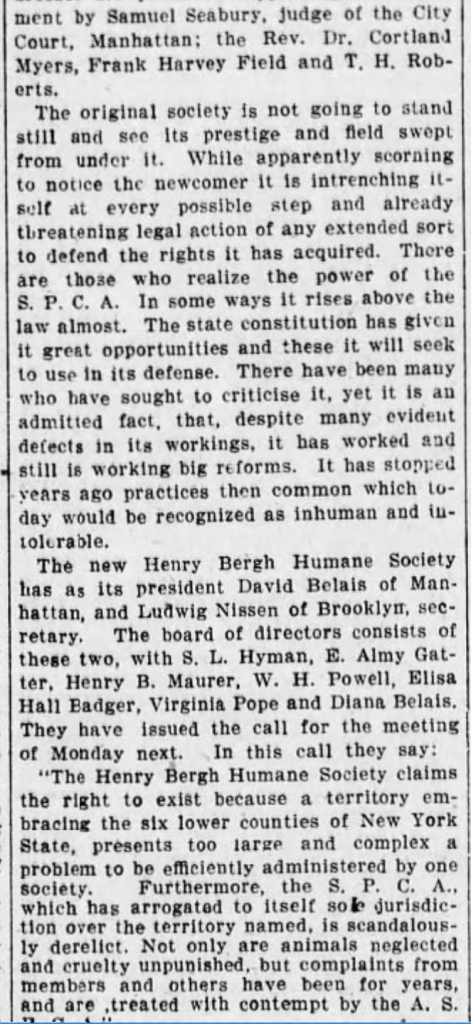

Still, the Society was the only agency providing animal care and control services with the city. In fact, it was legislated that they were the only society that COULD provide services. The article above references repealing an amendment, and that amendment is indeed the one that protects the A.S.P.C.A. as a sole provider of services in the city.

The second contributing factor was the operating budget of the A.S.P.C.A. itself. While many important changes for the care and housing of animals had come shortly after the A.S.P.C.A. took over the contract for municipal animal control, including the building of their new headquarters in Manhattan and several new shelters, the budget simply wasn’t keeping pace with the expanded workload. The new headquarters quickly became a target for those dissatisfied with the operations of the society, with newspapers referring to the marble building as unnecessary, opulent, and a waste of dog licensing money. People were still extremely angry about the new fee for dog licensing, which at this time was two dollars for a female and a dollar for a male, a hefty sum for a regular family.

Third was the fact that the some cruelty laws in the city were already becoming outdated and enforcing them was difficult. The Society had long taken the stance to not enact individual laws preventing specific acts of cruelty; this stemmed from Henry Bergh’s strong original belief in “one law to rule them all.” In other words, as long as it meant the definition of “unnecessary cruelty” the animal should, in theory, be protected. There would be no need to specifically prevent, say, tail docking. Specific acts were decided based on case precedent and the courts were continually making new decisions on what was, or was not, cruel. This was something that was slowly changing with John P. Haines now at the helm of the organization and Henry Bergh having passed away in 1888. The ineffective old laws that prevented immediate action in things like shooting a horse that was down injured in the street suffering without the owner present, which led to a society that was increasingly less tolerant of animal suffering watching as the legal barriers played themselves out, sometimes with an officer standing beside a suffering animal, taking no action.

Which leads us to our fourth point; wealthy high society members, who were the ones who truly controlled the media (and much else) in New York City, were angry about some of the newly passed cruelty laws that influenced hunting, such as the law against pigeon shooting that was enacted in 1902. These society members considered pigeon shoots to be an upper-class activity and they did not appreciate the ban. These angry society members were quite well connected to the press. A wealthy society advocate with a loud voice can be a fearsome thing, because they can choose to provide that voice to whomever they choose. And they did.

You can see that we’ve begun to have the perfect storm; The A.S.P.C.A. could not reasonably fulfill the duties they had been contracted to carry out. They didn’t have the money and they didn’t have the manpower. They were bound by antiquated laws, and as a result, animals in the streets were suffering in public view. Advocates began to take notice, and a collective of people determined to change things began to form. It’s these individuals that held the first private meeting on April 12, 1904 in the Nevada Street apartments. And while no notes exist of the first couple of private meetings, by May third, regular meetings at the Nevada, an apartment house with a large public ballroom, were open to the public.

At the head of the advocates was a gentleman by the name of David Belais, a manufacturing jeweler from Greenwich Village and a prominent member of the New York Vegetarian Society. The stated intention of the meetings were to form a new society, and at first, it was unclear specifically what the Society would do. Replace the A.S.P.C.A.? Work along side? They took the name “Henry Bergh Humane Society” both as a smite to John P. Haines, stating his jealousy over the original founder of the organization, and to publicly declare the new society’s intention to follow Mr. Bergh’s original level of visible activism.

From the jump, the articles covering the public meetings were very heated. When someone asked if anyone had met with the board of the A.S.P.C.A. to discuss their concerns, John B. Uhle of the City Highway Alliance (indeed, a city employee) replied “They are all a bunch of dummies, anyway.” From this moment, things escalate very quickly. The below article in the New York Times is indicative of what is to come.

Like all events, depending on which media source covered it, the story differed slightly. The below article in the New-York Tribune features the headline “SPCA Honeycombed, it is declared; New Society Meets.”

The use of the word “graft” was popular in the muckraking journalism of this time period. It means, in context, a gross misuse of funds, a abject neglect of duty; corruption. It was strongly associated with politics, politicians and power.

You’ll also see the strong high society association with the attendees, with many prominent women in attendance including Miss Belle Di Rivera, the head of the New-York City Federation of Women’s Clubs. It’s important to note that most people in this time period who had any free time at all belonged to a few “societies” that either revolved around cause or around special interest. Ms. Di Rivera was a suffragette and a recognized leader of the Women’s Club movement, and had the ability to use her voice to influence women all over New York.

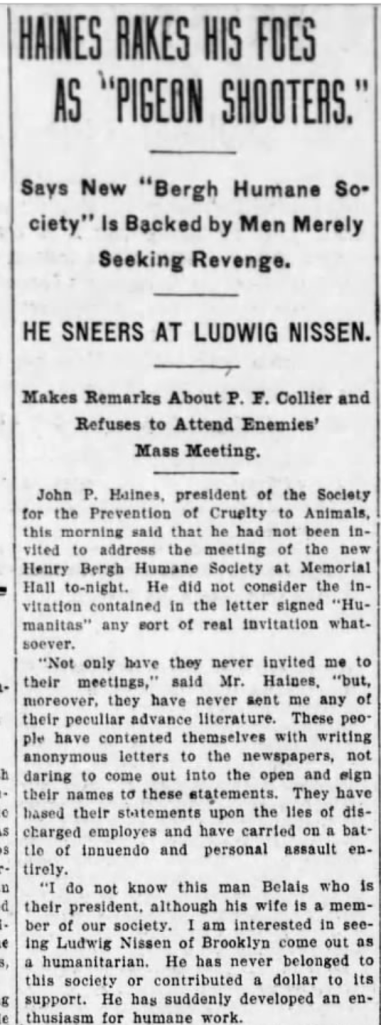

John P. Haines first ignored the advocates, but soon following the public meeting, he granted an interview to The New-York Tribune and made a short statement that the movement of the Henry Bergh Society was made up of “Former Disgruntled Employees of the A.S.P.C.A..”

By the 7th of May, plans began to emerge for the newly formed Henry Bergh Society to merge with another group of advocates in Brooklyn.

Mr. Belais immediately replies via the press, refuting these charges, and in another article (not included here) he openly invites John P. Haines to attend the next public meeting and state his case, although no formal invitation is ever sent. The invite is published in the newspaper only.

Simultaneously, tons of letters to the editor and spot pieces begin showing up across the city, highlighting the ineffectiveness of the A.S.P.C.A.,

By the end of May, the Henry Bergh Society has solidified it’s messaging: the “old society” was corrupt, no more than a charitable trust, and John P. Haines had ruined Henry Bergh’s legacy. It is now a money making organization that has no interest in fulfilling it’s duties, and the only solution is to appeal the amendment leaving them as sole contractors for New York and allow the “New Society” to work alongside.

Meanwhile, John P. Haines solidifies his messaging on the side of the A.S.P.C.A., stating that he has never been invited to any public meeting, the organizers of the new society are people who are either disgruntled former employees or society members angered at the outlawing of pigeon shooting. The new society members are inexperienced and don’t understand the weight and conduct of the current laws. They have taken a “sudden interest” in the humane movement and have “never been interested before.”

Next week, I’ll cover how the Henry Bergh Society develops an agenda for their work and how they attract, grow and retain a large constituent of advocates across New York City while also calling for an audit of the A.S.P.C.A.’s books. As always, I’d love to hear your comments and thoughts.

-Audrey

4 responses to ““Those Dissatisfied with the Conduct of Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals”: The Henry Bergh Society, Part One”

[…] June of 1904, in the midst of a round of slanderous newspaper articles (covered in part one of this story) surrounding John P. Haines, the A.S.P.C.A. Board of Managers issues a statement in the periodical […]

LikeLike

[…] you missed part one and part two of this story, check them out […]

LikeLike

[…] you’ve missed the first few chapters of this story, you can find those installments here: first, second, and […]

LikeLike

[…] you haven’t read the first few chapters of this story, you can find them here: first, second, third, and […]

LikeLike