By the time Elise Booth fell and broke both of her legs below the knee as a small child, the debate around whether or not shelter animals should be turned over for use in vivisection (the practice of performing operations on live animals for the purpose of experimentation or scientific research) was raging in the humane movement. In fact, the practice of vivisection was emerging as a leading topic of the Humane Movement (and the Reformer movement) in the United States. I’ll offer just enough background to explain the article, but I’ll also include some sources at the end for future reading.

Caroline Earle White and her friend Mary Frances Lovell, who had both founded both the Pennsylvania SPCA (with their husbands) and then later founded the Women’s Branch of the Pennsylvania SPCA, had taken up the cause of vivisection in 1883 after receiving demands by doctors to turn over pets from the city’s shelters for use in experimentation. What followed was the formation of the American Anti-Vivisection Society, which initially worked to restrict the work of vivisectionists and later shifted its mission to eliminate vivisection completely. In 1885, the first US bill to regulate vivisection (The Bill to Restrict Vivisection) was submitted and failed to pass after intense opposition from the medical community. This was despite an extremely similar bill passing in the United Kingdom just years earlier. Many people chalk the failing of this bill up to the fact that the magazine “Science,” which was widely read and respected by the medical community at the time, was opposed to the regulation, and very actively published pieces steering the views of the medical community as a whole on the topic.

At the time of the publication of the articles below, which was 1897, vivisection was not regulated in the state of New York aside from being subject to the wider original anti-cruelty act of 1866, and was interpreted to limit experiments of “unjustified harm.” Cases in New York regarding cruelty in this context had been tried, and in practice, vivisection had been limited to occurring in educational settings only. There would not be sweeping legislation to regulate vivisection until the animal welfare act of 1966.

The use of shelter animals in experiments, although the catalyst for the formation of the AAVS itself, was a sub-section of this wider debate, and the act of giving animals for use in experiments depended strongly on the locale being asked for pets. Some gave animals, and some outright refused, and some shelters decided on a circumstance by circumstance basis. In this particular instance, as outlined below, John P. Haines refused although he himself was not entirely anti-vivisectionist and leaned more toward regulation.

It’s extremely important for those in our movement to know and understand that shelter pets are still used in medical experiments today. Many states have laws that still require the surrender of pets for experimentation and you can find a list of those states here: https://aavs.org/animals-science/laws/pound-seizure-laws/

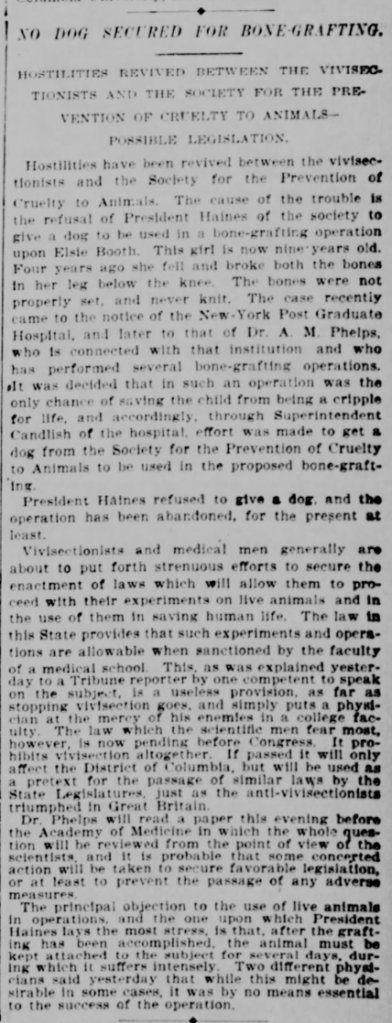

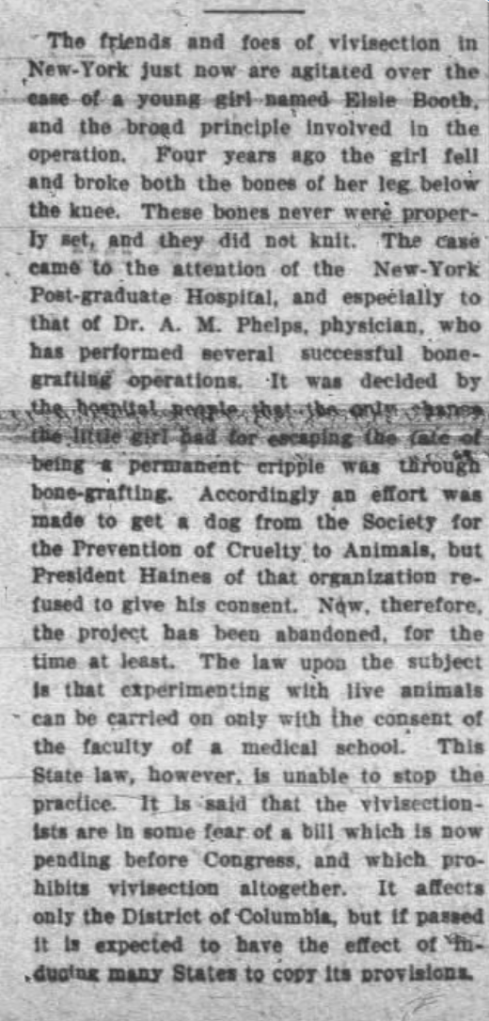

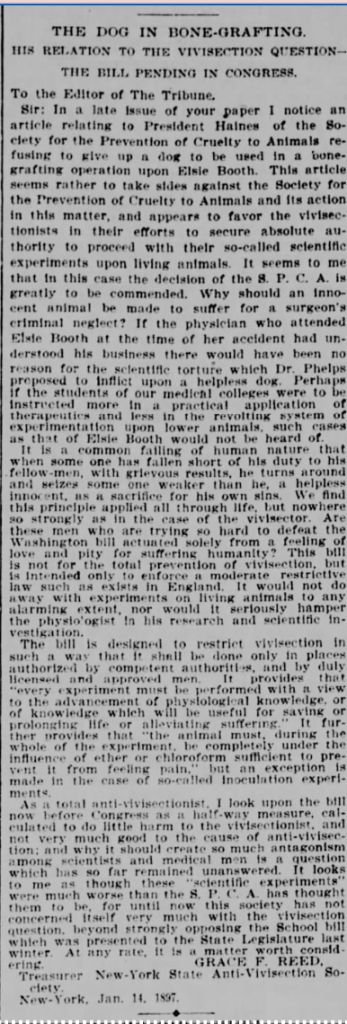

Below you’ll find several articles about Elsie Booth, a child who was permanently disabled by a fall, and the debate surrounding the acquisition of a dog to be used for a bone graft and a letter to the editor submitted to the Tribune following the publication of the article by Grace Reed of the New York Anti-Vivisectionist Society.

Cases regarding the use of animals in specific instances designed to evoke emotion commonly made the newspapers to garner attention to the issue. This is particularly true in the case below, published when a regulatory bill was pending in Washington DC.

I’ve tried my best to be factual here without being gory because I myself find this topic hard to read about and I do have a goal of making this content educational without being traumatic. This is, for the most part, a blog read by industry folks and we have enough trauma. The cruelty subjected upon the animals used in these experiments is absolutely unimaginable. That being said, this is a practice that continues to impact animal shelters. It’s important that we understand how it started so that we can end it, and there is strength in seeing how the very people who founded our movement outright refused to turn animals over to vivisectionists. It was wrong then, and it’s wrong now. If you’d like more information on changing legislation in your community or state around surrendering shelter animals for vivisection, the American Anti-Vivisection Society still thankfully exists and is still carrying the burden of ending vivisection. You can find them here and get help.: https://aavs.org/

-Audrey

New-York Tribune, January 11, 1897:

Buffalo Courier Express, January 12, 1897

New York Tribune, June 15, 1897

Resources:

The Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 (full text, UK) — the landmark British statute that first regulated animal experimentation (useful as a primary legal source). Legislation.gov.uk

Vivisection in Historical Perspective (ed. Nicolaas A. Rupke, 1987) — an edited collection that places the 19th-century vivisection controversy in wider scientific and social context; good for scholarly background and historiography. NLM Catalog+1

“Animal Experiments in Biomedical Research: A Historical Perspective” — N. H. Franco (2013, PMC review) — an accessible open-access article tracing the long history of animal experimentation and the public debates around it. PMC

Anti-Vivisection and the Profession of Medicine in Britain (A. W. H. Bates / Open Access book) — a focused social history of the British anti-vivisection movement from the nineteenth century into the twentieth; strong on physicians’ responses and professional ethics. OAPEN Library+1

American Anti-Vivisection Society — “Our History” (AAVS) — institutional history and primary-source material about the founding and early campaigns of the first major U.S. anti-vivisection organization (founded 1883). Useful for the American story and primary documents. American Anti-Vivisection Society+1

The Animal Research War — P. Michael Conn & James V. Parker — a readable account (and primary viewpoint from a scientist) of later 20th/21st-century controversies and activist tactics; useful for how debates evolve into the modern era. Amazon+1

“A history of animal experimentation” — Cambridge University Press (chapter in Animal Experimentation, 2017) — a scholarly chapter giving a careful overview of the origins of vivisection in Europe and its institutionalisation. Good for teaching-level synthesis. Cambridge University Press & Assessment

“Vivisection, Virtue, and the Law in the Nineteenth Century” (NCBI / book chapter) — examines moral arguments and legal responses to vivisection in 19th-century Britain; excellent for ethics + law intersection. NCBI+1

“Medical science and the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876: A re-examination” — M. A. Finn (White Rose Research Online / PDF) — a scholarly re-examination of how the 1876 Act affected provincial British science and anti-vivisectionism. Good for detailed legislative impact analysis. White Rose Research Online

“Vivisection Ancient and Modern” — Gary B. Ferngren (2017, History of Medicine journal, PDF) — traces vivisection back to ancient medical practice and compares ancient and modern arguments; useful for very long-range perspective. historymedjournal.com

Document collections: Animal Welfare & Anti-vivisection 1870–1910 — multi-volume primary-document collection (campaign literature, pamphlets, letters) for nineteenth-century researchers. Great if you want primary sources and contemporary pamphlets. Google Books

Selected scholarly articles and case studies — e.g. “We must perform experiments on some living body: Antivivisection and American medicine, 1850–1915” (Hausmann, Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era), plus JSTOR/book chapters on the Vivisection Act’s administration and its cultural ramifications. These give focused case studies. Cambridge University Press & Assessment+1