On December 31, 1895, The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals issued it’s thirtieth annual report encompassing the operating years of 1894 and 1895.

Following the opening of its second location in Brooklyn, the organization was expanding rapidly under the leadership of President John P. Haines. Prominent issues of the time included ear cropping for dogs, prosecuting individual cases of abuse, humane slaughter for horses and other livestock, issues concerning carriage horses, water fountains, issues concerning purebred dogs, and pigeon shooting.

The Brooklyn location, which was newly built, was housed in a donated (and highly renovated) stable and railcar building on the corner of Nostrand avenue and Malbone street, and had received much press in the newspapers – much more so than the original Manhattan location. The opening was covered extensively by multiple periodicals, which included articles on everything from society fundraisers, to tours, to the new process for licensing the animals, to the new law allowing animal control to pick up cats. And, of course, the “death chamber” and “illuminating gas” that offered a “painless” death to the animals that entered its doors. The shelter was touted as the most sophisticated model of humane care, and the ASPCA was exceptionally proud of the work they were doing there.

In February and March of 1886, coverage for the annual report began to make the newspapers because of the presentations of the report in society. The actual report itself, which would have been published both independently and included in “Our Animal Friends” is a fascinating read, and I’d encourage you to take the time to check it out.

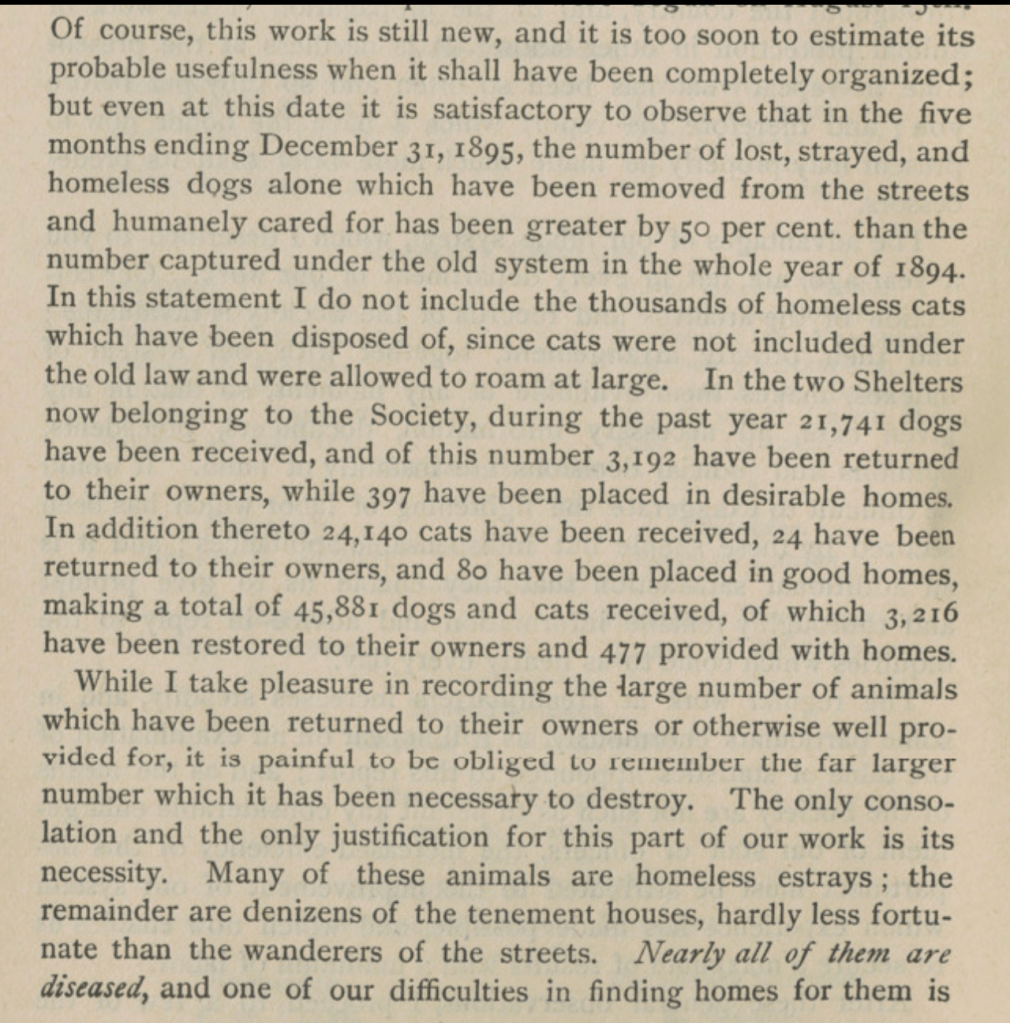

There’s one stand out portion that I’d like to talk about here today – and that’s some of the first data collection we have in the humane movement of intake and outcome data from specific shelters. John P. Haines, as President, was an extremely diligent cataloger of information and worked hard to improve tracking of various metrics for the organization. For that we are lucky. There is a section of the report that focuses on early shelter data in his opening letter:

The shelter had opened for operation in August, and by the time the report was published, the “number of lost, strayed and homeless dogs removed from the streets had increased by 50%.”

Included also is this table, outlining the quantity of animals destroyed by the organization. It’s of note that although this presents as a drastic increase from 1894 to 1895, that is when the ASPCA took over animal control from the city, and therefore primarily became responsible for the killing of pets. It’s extremely important in understanding the movement to continue to recognize that this killing is presented as both part of the essential duty of the organization AND as a kindness. This is another example of there being no expectation or goal of live outcomes; something that would not change until the no kill movement began in the late 1970s.

Now, let’s look at how this information was reported out to the public in the papers. Here’s an excerpt from the New York Herald, March 2 1896.

And another example from later that same week, from the Brooklyn Eagle. Of additional note here is the statement from Haines about the large disposal: “The only consolation and the only justification for this part of our work is it’s necessity. Many of the animals are diseased, and human diseases are undoubtably propagated through them.” This is illustrative of the lack of understanding of germ theory that drove so much of the initial intake of all stray animals. The timeline between this report and Louis Pasteur’s discovery of the rabies vaccine is months apart. We also start to see “disease” begin to be used as a justification for killing in articles that show up about this timeframe. The ASPCA was under significant pressure to operate more professionally than the city dogcatchers they had taken animal control over from. While there had not been a call for more live outcomes, there HAD been a call by citizens for more humane treatment. My own opinion is Haines is specifically calling out the disease as part of that promise of humane care.

So that you don’t have to do the math – the dog live release here is about 17%, while the cats come in at about .04%. Note that this is also the first year in which animal control was contracted to also bring in cats.

This period from 1894-1896 is an extremely pivotal one for the humane movement. Many of the things presented in this report as fact or necessity became foundational policies that still exist in shelters today – and I’d love to know what you see either in the articles or in the annual report.

-Audrey