Nothing will immerse you in a period of time in history faster than reading periodicals pertaining to a movement, and this is especially true of periodicals from the gilded age. At this point in history, the linotype model printing press had been recently introduced, greatly speeding the ability of publishers to quickly and cheaply produce printed material. The application of electricity also allowed for periodicals to be easily cut, folded and stapled by publishing houses. This led to the ability for any movement that wanted a periodical to have one, and have one, they certainly did.

As the gilded age ebbed into the 1910s, the animal welfare movement began to change. Chapters of the ASPCA, George Angell’s Brave Bands and other anti-cruelty societies and sub-societies had sprung up around the country. No longer in it’s infancy, the movement was gathering attention and support thanks to the many tireless advocates dedicated to their causes, with most cities having some kind of chapter dedicated to the protection of animals. In the United States, the mail service was extended to the whole country in 1900, allowing news to travel. Print media was one of the primary ways animal welfare societies communicated with supporters and raised funds, and most of the larger societies published something.

Among the advocates of this time was Caroline Earle White. Caroline was critical to the animal welfare movement for so many reasons and deserves much more than these short paragraphs. Her name is familiar to many in the field as the founder of the animal welfare movement in Philadelphia; With her husband, attorney Richard P. White, she founded Pennsylvania SPCA and then (because a woman could not serve on the board of the “official” SPCA, a women’s branch of the same organization, Women’s Pennsylvania SPCA. Both organizations still exist today and are considered the first true animal shelters.

Caroline also and importantly founded the American Anti-Vivisection Society in 1883, at the advice of British Anti-vivisectionist Francis Power Cobbe. Caroline received a letter from physician S. Weir Mitchell requesting live dogs for vivisection in the name of science. She was, of course, horrified and the anti-vivisection movement became her greatest passion and, arguably, her life’s work.

Vivisection, is (loosely) the use of live animals for scientific study, very often involving live dissection. It is as horrific as it sounds. And it is still very much legal, for anyone curious. For the sake of this article I am not going to further describe it. Mainly because this blog is supposed to be for animal welfare workers and we have enough trauma. However, there is plenty of information out there – you should not have any trouble finding it. Suffice it to say that the American Anti-vivisection Society fought bravely and tirelessly against the use of live animals in dissection, primarily to lobby for awareness and humane standards for the animals used.

The Journal of Zoophily was their periodical, distributed to chapters across the United States. The word Zoophilic, in itself, means having an affection or attachment to animals. I personally wonder if the use wasn’t also selected because of the “Phily” for Philadelphia. It was printed monthly in conjunction with the Women’s Branch of the Pennsylvania SPCA and featured all manor of animal welfare stories. Caroline Earle White served as Editor and Chief, signing pieces “C.E.W.”

Zoophily gives an absolutely fascinating look at the mechanics of the movement during time period, and I want to use the remainder of this space to let you see a few I’ve selected that I thought were particularly interesting.

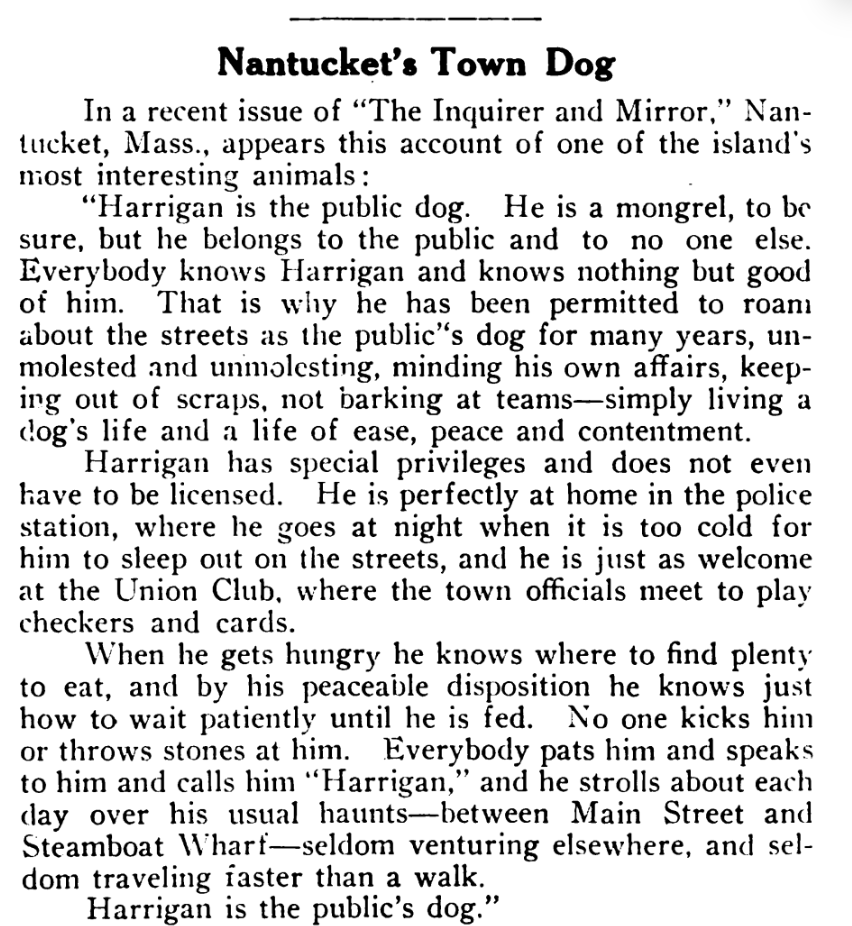

The first piece is about Harrigan, a stray dog who lives in Nantucket. Zoophily commonly argued for humane treatment of street dogs and often protested the need to bring dogs in to the shelter at all. It seems that Harrigan was doing just fine on his own.

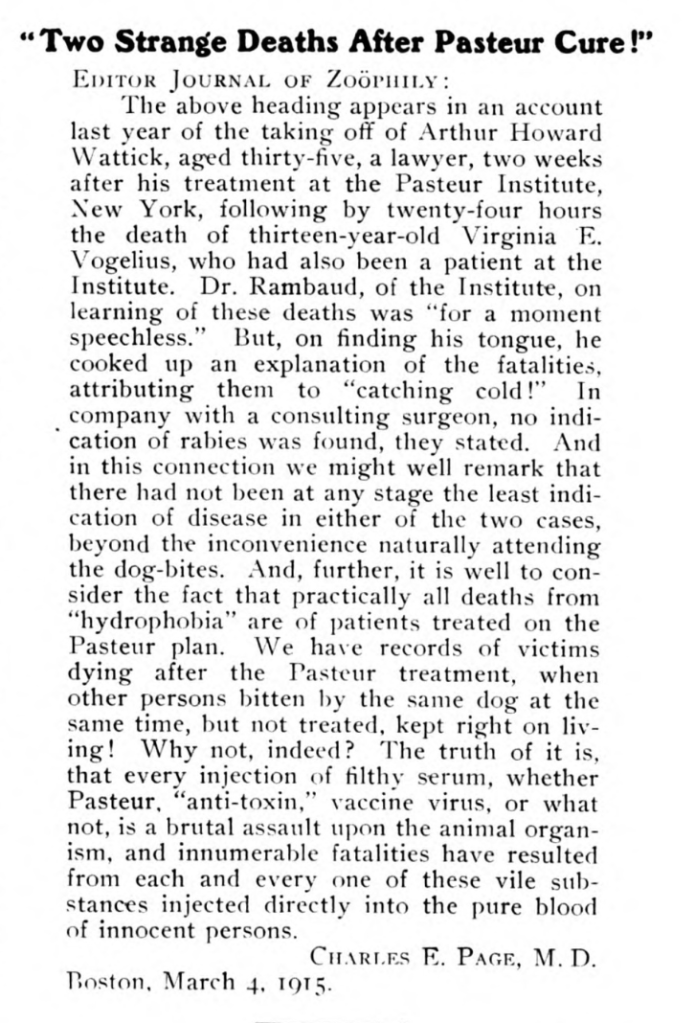

Zoophily often also discussed the effectiveness of the Pastuer treatment and was quick to point out that most dogs that bit people were not rabid, and could be held in shelters and observed for signs of rabies instead of being destroyed and tested. The periodical often also questioned whether rabies or hydrophobia was real at all, and argued that people who were bitten were also just as apt to die of “Lyssophobia” or the fear of rabies itself. There were often also articles questioning the effectiveness of vaccines.

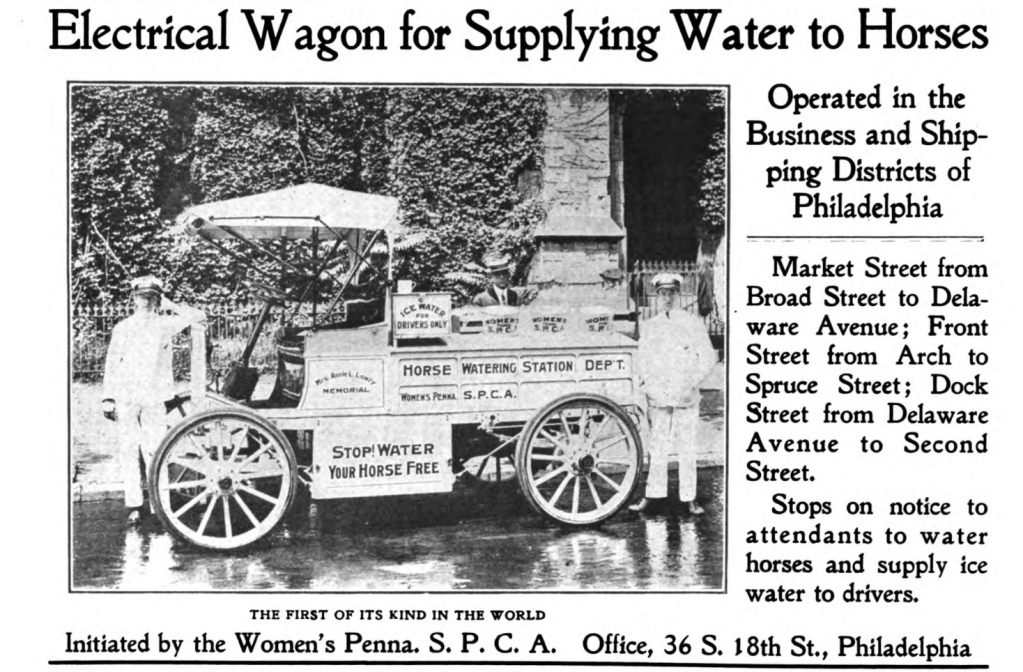

Of course, news of progression of the movement also was common. One common piece of work that humane hocieties of all sorts conducted was the installation of watering fountains and watering stations for horses.

Here we see a report of work from Women’s for the previous month, which would have been March of 1915.

And here we have an advertisement for a free clinic; If this isn’t proof that intake diversion isn’t a new concept, I don’t know what is.

And I’ll leave you with this short mention of a thief in Paris.

I could go on pretty much indefinitely with these articles, but I’ll leave you with these. and hope you found them enjoyable. If you would like to check out issues of Zoophily for yourself, many issues are available for free on Hathitrust and reading them makes for an especially enjoyable evening. If you do check them out, I’d love to hear what you thought.

-Audrey