Full admission that this post is about early “cures” for rabies (hydrophobia.) It has little to do with the animal welfare movement and everything to do with my obsession with hydrophobia and history. You will have to cut me some slack this week. I’m at a conference in Las Vegas, which, in my opinion, is possibly the worst place in the world. In that, my writing time is limited and I’m feeling very overstimulated.

That being said, it’s fair to say that in these cures it’s easy to see the terror that people had of hydrophobia. To die of it was to die a terrible, prolonged, and painful death and all who were bitten knew there was no hope. Since rabies has an incubation period of several weeks to months, anyone bitten would wait anxiously to see if they would fall ill, knowing they would surely die if so. Pre-Pasteur treatment, doctors, who generally rarely saw hydrophobia because of its rarity, had very little information available to help them. They relied on folklore, depletive medicine, ambiguous information and the word of mouth and treatises of their peer group. Many people even wrote into newspapers with letters describing new cures they had heard of as a way of sharing information. It was quite common for favorite cures to be published. These attempted treatments were often about bringing a sense of hope to both patient and family more than anything else, especially because even the drugs available to keep patients comfortable were ineffective against the virus.

It’s this terror of a death from rabies that drives some of the very extreme policies around stray dogs that begin to take shape during the period between urbanization and vaccination. It’s also from this terror that the idea of bringing every single stray dog to a shelter gained traction. We’ll talk about that another time. For now, let’s just look at some of the treatments and cures that existed prior to the vaccine. It would be impossible to get them all in one post, but here are some of the more interesting early cures.

Some of the earliest recorded mentions of a cure for hydrophobia involved using a piece of the animal who had bitten you. A few of the more well known examples came from a Roman naturalist named Gaius Plinius Secondus, or Pliny the Elder, to his friends. It’s to him we can attribute the cure of taking some fur from the tail of the offending animal, charring it, and placing it in the wound. This is also the origin of the phrase “Hair of the dog that bit me.” He further advocated for “removing the worm found under the dog’s tongue.” We know today that he was referring to a ligament – unfortunately this practice was wildly adopted and was, ironically, known as worming.

Similarly, Ge Hong of the Jin dynasty (300 CE) recommended application of the brains of the offending dog to the wound. Another highly recommended cure was eating the liver of the dog that bit you, although it’s origins are a bit dubious.

There are also cures steeped in religious beliefs. Clay tablets unearthed in Iraq that date back to the 20th century BCE outline specific incantations to pray over a victim that basically amount to “we know there’s nothing we can do for you, but we are praying anyway.”

An Abbey in Liege, Belgium, also became the unlikely epicenter for rabies treatment. Saint Hubert, generally known as the patron saint of hunters and a name some in the animal welfare field will recognize, was the first bishop at this abbey. According to legend, he was visited by the apostle Peter along with several angels, and given a golden key and a linen stole.

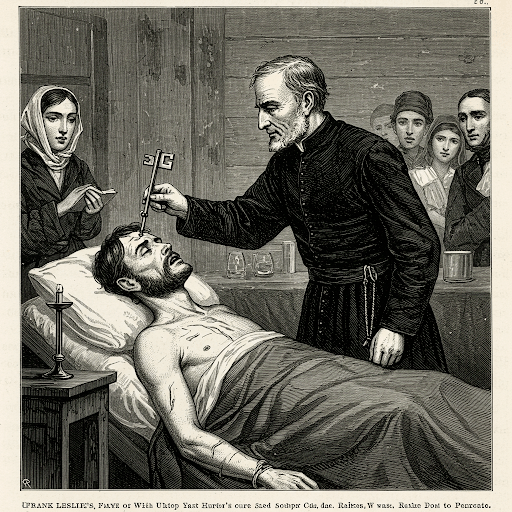

He was told that his special powers would allow him defense against evil spirits, and then soon afterwards it is said he cured a man from the bite of a rabid dog. This was known as “Saint Hubert’s Miracle.” Later, Monks at Saint Huberts Alley created “keys” shaped like nails or rods, which could be hung on the walls of homes for protection.

Or, if you had indeed contracted rabies, the nails could be heated to red hot and pressed into the wound. Interestingly, this cauterization may actually have been effective in curing the disease, depending on it’s application. This treatment was often applied by monks and later priests, who also performed a ritual where they would make a cut in the forhead, insert a linen thread “taken from the stole” and bound the wound in a black bandage for nine days. The power behind this folklore was so great that even as late as the 1920s, there are recorded instances of people refusing the Pasteur treatment in favor of this ritual, which was known as cutting.

Depletive medicine and the balancing of the “humors” or “sauces” in the body also offered some early cures. A text that is one of my personal favorites (like I said, I’m not fun at a party) is called “An Essay on the Bite of a Mad Dog” by a gentleman named Daniel Peter Layard, MD in 1768. This essay first examines the pros and cons of various commonly used tactics in depletive medicine, such as the use of emetics or bleeding the patient. He examines several cases and contrasts their success with the cure.

He then follows by then giving his own recommendation for a commonly recognized cure; Throwing the sick person into the sea. Bringing the humors back into balance was viewed as crucial to restoring health. Doctor Layard was of the opinion that the shock of being bitten was what caused the imbalance itself, and so further, the shock of being tossed into the sea was a likely restorative, especially given that a primary symptom of hydrophobia is, of course, hydrophobia – the fear of water.

Dr. Layard examines one particular case in which a man is shocked into a rabies infection by being bit by his own beloved cat, who was earlier infected with the virus by a known rabid dog. His friends, seeking a cure, carried said gentleman all the way to the sea, where he was tossed in and, assumedly, cured.

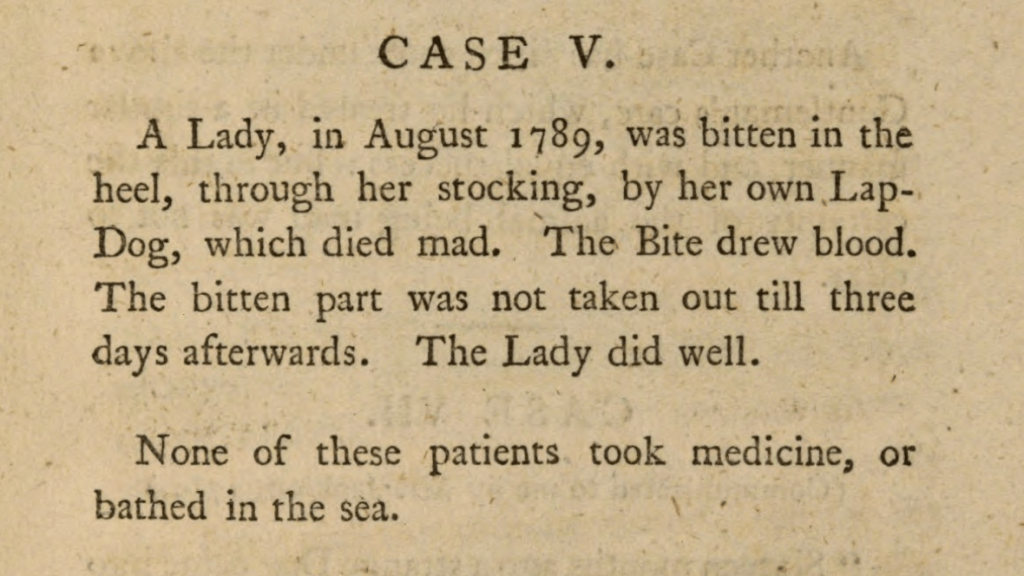

Of course, some people felt that throwing the bitten into the sea was not effective and pointed this out directly in case studies. See this excerpt from “A plan for preventing the fatal effects from the bite of a mad dog” (a common title) with cases by Jesse Foot, circa 1788.

And that, friends, is the time I have for this exploration. I feel certain that “Things that Don’t Cure Rabies” will become a regular series here. I’ll leave you with that; and if you’re at the Humane World for Animals Expo in Las Vegas, come find me and say hello.

-Audrey

2 responses to “Throw Him in the Sea or Some Early Things That Didn’t Cure Rabies.”

My admiration of you has grown! I love medical history, especially animal-related. This is fantastic so please keep it up!

Best wishes,

Jill Bradshaw

LikeLike

[…] to be fascinating to me. If you want to read some other posts on this topic, you can do that here and […]

LikeLike