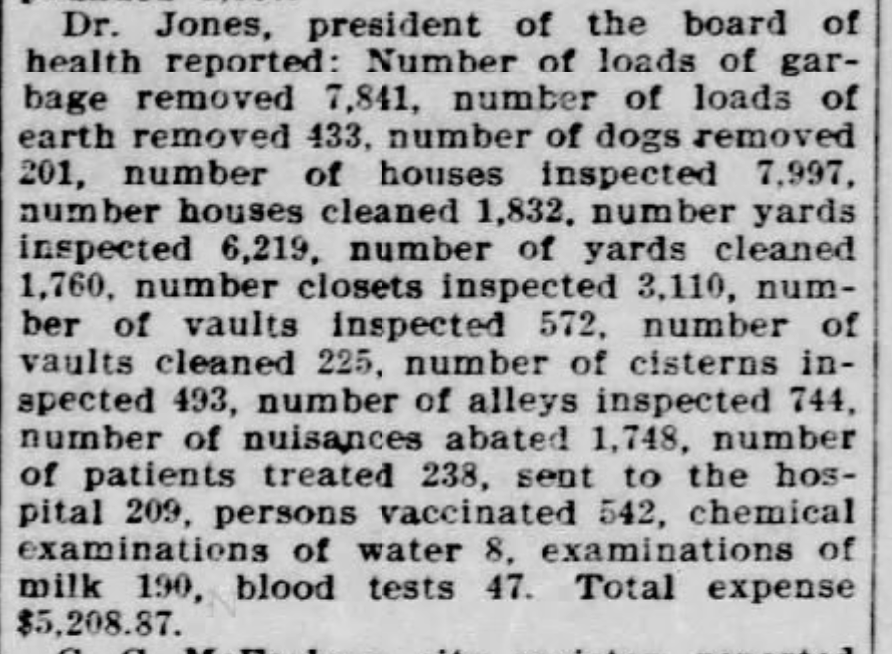

Under the headline of “Old Business Cleared up” in the January 19, 1900 edition of the Memphis newspaper “The Commercial Appeal” we find a report from the health department. There, sandwiched between the removal of garbage and the inspection of alleyways, we find “number of dogs removed: 201.” They did mean, of course, strays.

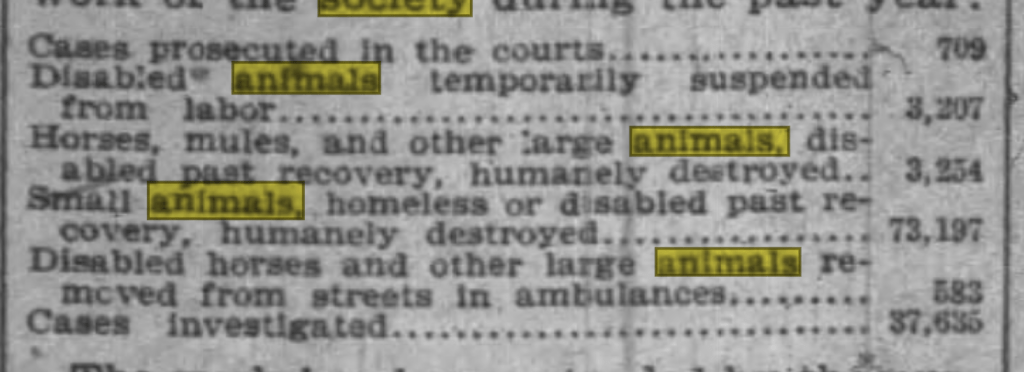

“Intakes,” as we call them today, were often reported in this way. Following the path of removal of stray dogs in the United States, time had moved them from community driven solutions to animal problems pre-1800s, to fear of rabies combined with tenement housing and overcrowding driving municipalities to institute the first stray dog bounties beginning in the 1830s, to the eventual “dog brokers” and fears over the moral corruption of children cashing in on unfortunate strays, to the first employed municipal dog catchers clubbing strays to death, to the eventual birth of the humane movement in 1866. By around 1900, animal control had settled into a comfortable rhythm for animal management in most major cities. Stray dogs were still considered unsanitary, potentially rabid, and dangerous, and were unilaterally accepted as a nuisance to be removed. Managed (generally) either by hired municipal dogcatchers who often were corrupt and likely paid by the number of animals brought in (and sometimes paid by the number of animals killed) for their work, or, in some places, in joint efforts with newly formed SPCAs and Humane Societies. Public-private partnerships had begun to hold, partially due to public outcry over the actions of both dog brokers and municipal departments, and now there were many examples of privately run agencies serving as animal control. The agreements looked then much as they do today. Contracts were for housing and care, often for a set number of days before destruction. Much less corrupt in their methodology out of the gate, but still highly focused on public safety and the belief that every stray must be removed from the streets, they reported their stray intakes in a slightly different way. Because they were contracted, they had to justify their work. One way they did that was through the numbers of animals brought in and destroyed. Below is a segment of the annual report of the ASPCA from 1897. “Homeless or disabled past recovery” precedes the number of small animals destroyed. Note the language and its slightly more humane tilt.

The number of dogs removed from the streets and brought into the shelter system, regardless of outcome, had become not only an accepted, but also an expected measure of a shelter’s effectiveness. It was also a measure of their ability to treat animals humanely.

See below this enthusiastic letter to the editor from the Record-Argus in Greeneville, Pennsylvania, April 29, 1897, by way of example.

Author John Green is quoted as saying “Nothing is so privileged as thinking history belongs to the past.” This particularly applies to the current culture around intake as a measure of effectiveness in animal shelters. The industry still unfortunately considers intake the default and expected service option for animals in need of accessing animal services, even though the historical reasons for intake as a default have largely been eliminated. We still calculate budgets and contracts based on animals over the threshold of the doorway, with housing and control being the service defined as “necessary.” While it is extremely important that we accurately capture the number of pets moving through our shelter systems between the actions of intake and outcome, it’s also important to consider the reasons that led us to believe that intake for every pet was the most appropriate service option to begin with and whether animals taken in is still the most relevant measure of a successful animal services program in a community. Possession is no longer necessary or logical for all animals to access some of the most effective animal services programs, such as low cost vet care, safety net housing, food pantries and shelter supported home to home rehoming. These are the services that keep pets out of the system, preventing it from becoming overwhelmed and resulting in shelter death. If the pet facing shelter intake has a home if a solution is provided for retention, finding them a new home doesn’t solve the problem. In that equation, intake is not the answer.

Conversely, the many pets experiencing cruelty, neglect, abandonment or other challenges that are entering the shelter because they do need the services provided by intake deserve to live; no kill for animals who are savable should be (and is thankfully becoming) a minimum standard of care.

Pets have a fundamental right to leave the shelter alive whenever possible, and to never enter the shelter if it can be prevented by keeping them with their families. It is my opinion that live release rate will remain the North Star of animal shelters until we stop killing pets for lack of resources or for unwillingness to progress and meet industry standards; to truly have no kill, we have to create communities where killing animals for space and time becomes inexcusable, not because it is illegal, but because it’s unilaterally accepted as unnecessary and immoral. To do that, we need to protect and reinforce accountability to live release. We must have excellent in shelter care, barrier free access to pet acquisition, and programs to move shelter animals through the system efficiently and effectively.

We must also define what are the most progressive, the most humane, the most effective programs to support community members who want to keep animals out of shelters. We need to begin to change the vision of intake as a default or even a primary service of animal services. This sets a vision for a future where the only animals ever entering the shelter are those with no other option, and intake is a last resort, not a default. That’s a future where the industry of animal sheltering looks different for all of us. In the end, animal shelters as mechanisms for management are social constructs that were built upon issues that do not look the same today as they did 150 years ago. Shelters today need to align to solve the problems of today. Let’s save every savable pet entering the shelter doors and do it very well. Let’s also create a world where they rarely have to come in at all.

-Audrey