Good morning, friends.

In light of recent events, I’ve decided to take a break from the heavy-heavy and bring you something I’ve been saving for a rainy day; the topic of mad stones. I find them to be endlessly fascinating, and I hope they’ll serve as an excellent distraction for you as well.

While there’s not a strong correlation between mad stones themselves and animal welfare policy, what they do demonstrate is the quest for a cure from hydrophobia (the term for rabies occurring in people) and the great lengths people would go through to attempt to heal someone afflicted. Whenever I speak on the topic of the influence of rabies on animal control policies, I attempt to convey the absolute terror the bite of a dog would inflict in people, knowing hydrophobia had no cure, and how that led to the pressures put on municipalities to round up every single stray dog. Part of this terror was the confusion surrounding the disease itself. It’s from that confusion and fear that many folk remedies came to be used.

One of the more unusual folk remedies is the mad stone. A mad stone was generally a bezoar (yes, like in Harry Potter) taken from the stomach of a cud-chewing animal, most commonly a white tailed deer.

There’s a long history of the use of stones and crystals (called lithotherapy) in medicine that dates back to the middle ages, and mad stones in particular are historically believed to have originated in Asia and traveled through to Europe along trade routes and then across to America.

In Northern Scotland, mad stones seemed to have taken a particularly strong root. Many clans document use of mad stones in their family records and several are documented to having been lent to a display in 1908 called The Highland Exhibit. It’s from this location that they possibly traveled to the United States.

In particular a documented story of a family in Virginia with the last name Fred is said to have immigrated to the US from Scotland in 1776 with a mad stone in their possession which supposedly saved “140 souls.” This story was originally published in Saint Nicholas magazine in 1909.

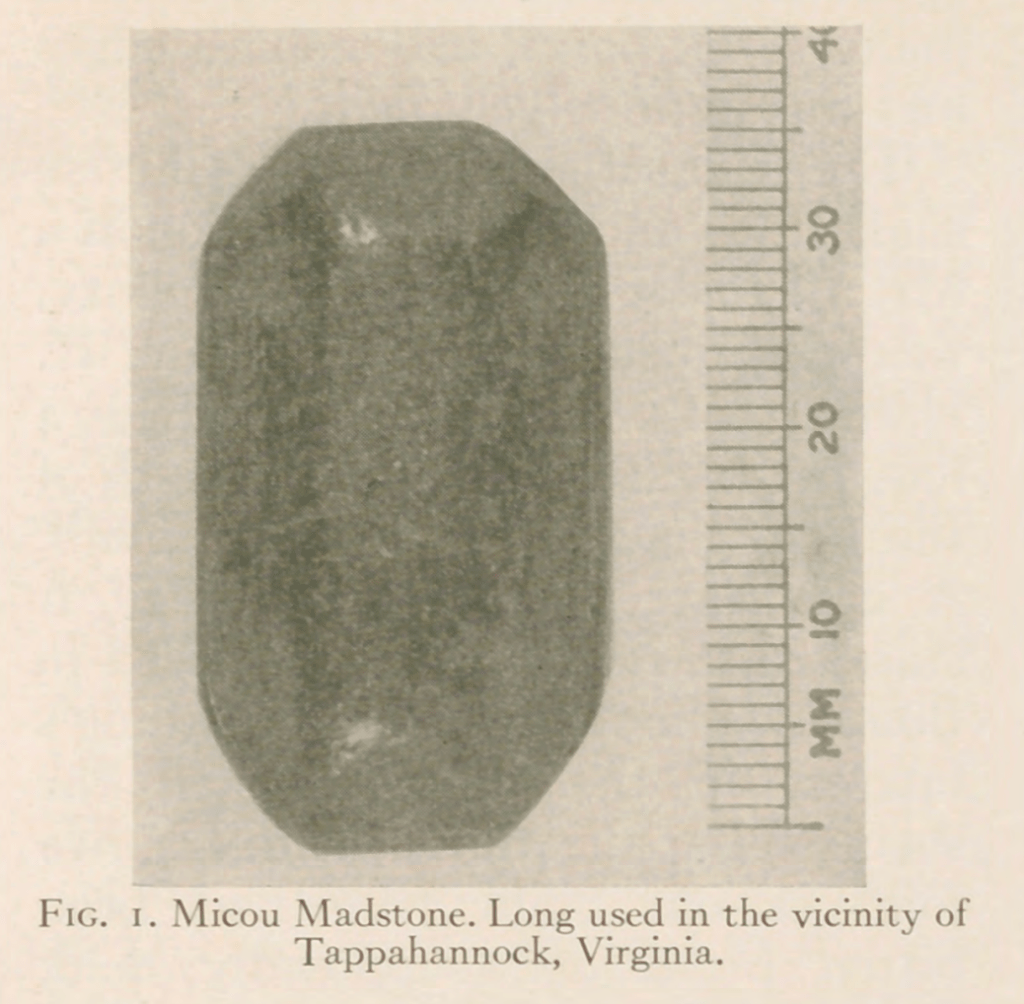

Some other interesting stories of specific mad stones can be found in a 1934 paper by Wyndom B. Blanton, MD, of Virginia.

Below are images of two of the more well documented stones from this paper.

The word bezoar itself is believed to have come from the Persian word “padzahr” which means “expelling poison.” This type of remedy was originally used to protect royalty from poison in various forms. I’ve read that the term “mad stone” itself was probably American in origin, although I don’t have a way to substantiate that. Mad stones were also sometimes referred to as “snake stones or serpent stones” in the earliest written references, most likely because very early references do not identify them specifically as bezoars, but as “stones from the heads of snakes.”

In order to use the mad stone, when someone was bitten by a rabid dog, the stone would be applied to the bite. It supposedly drew out the poison, thus healing the bitten.

There are many varied accounts to its appropriate use, but most involve using milk – the very early stories include using human milk, but by the time the stones reached America, any milk seemed to do. The most common application I have seen was to soak or boil the stone in the milk, and then apply it to the bite and leave it for several hours. It would stick to the wound and draw out the poison, eventually turning green. When it “fell off” it was washed in milk until the milk itself turned green, which supposedly extracted the poison from the stone, cleansing it. I’ve seen that supposedly the milk would bubble during this process, and the bubbles were an indicator of progress to the poison being removed. The stone could then be reapplied as many times as needed.

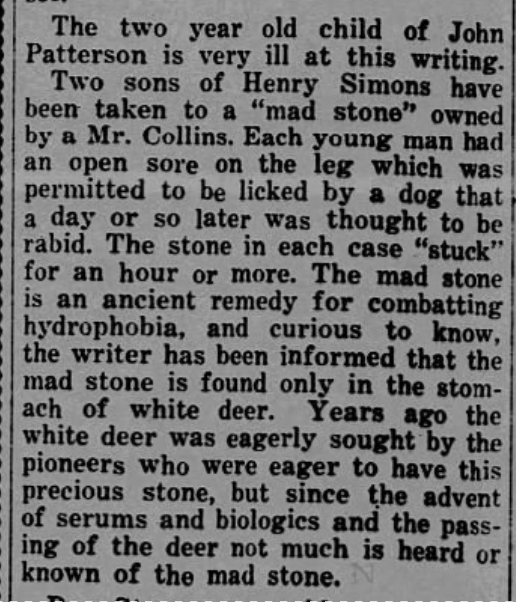

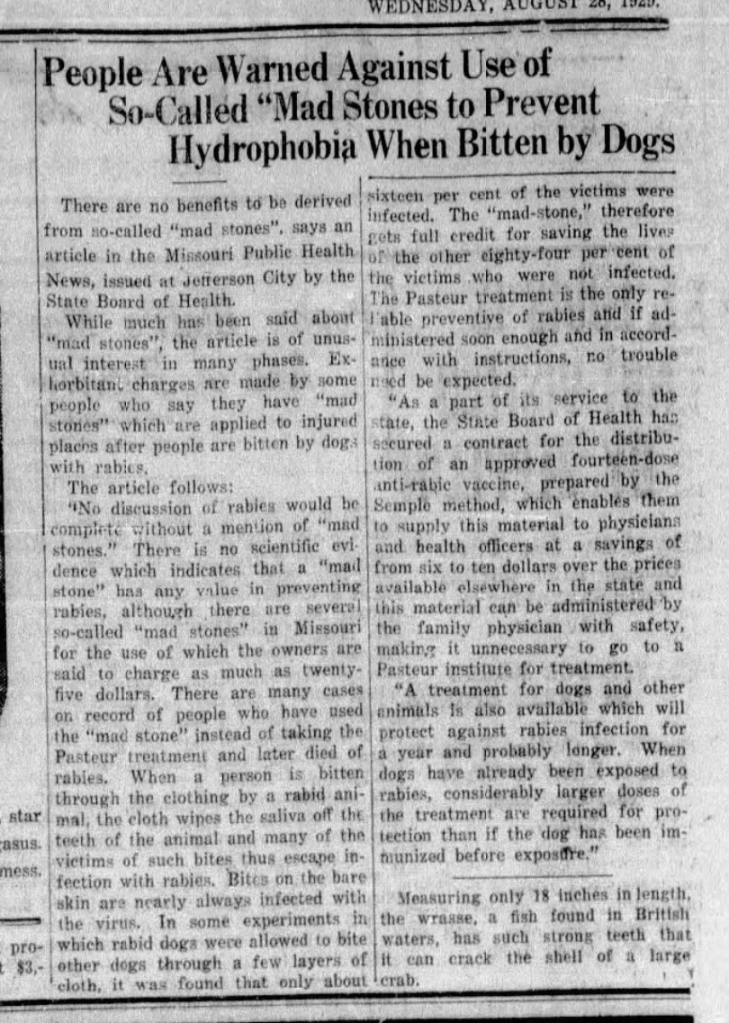

From the Democrat-Argus, September 13, 1929.

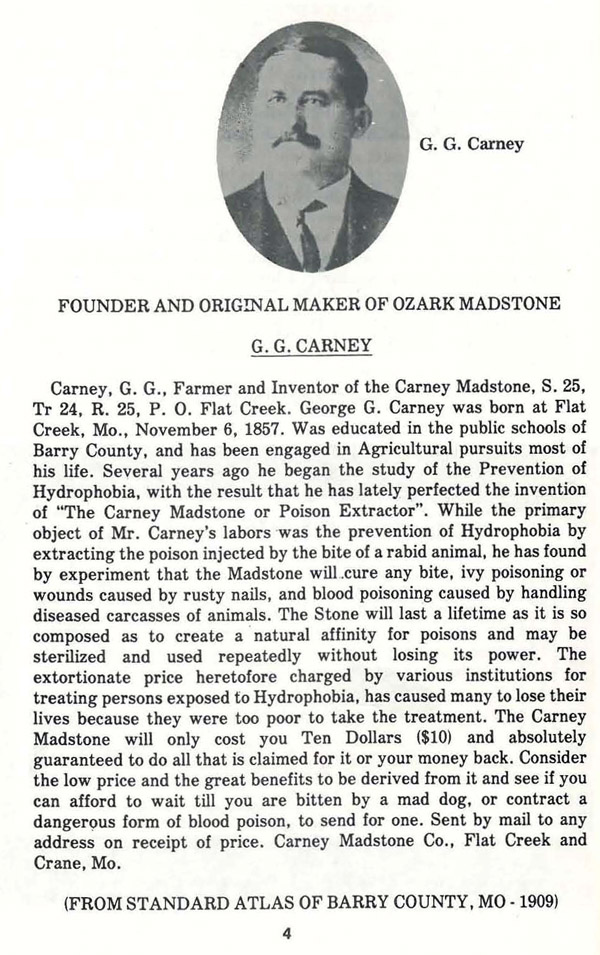

Mad stones were especially popular in the southeastern, mid-western and Appalachian regions of United States. The Ozarks, in particular, had a strong tradition of mad stone use, so much so that a gentleman named G.G. Carney attempted to make a sort of business of them.

Mad stones were often kept by and handed down in families and sometimes had extremely detailed origin stories themselves. I’ve found mixed information about their being available for use for free or about exorbitant charges to use one. Like anything else, this probably just depended on the locality and the motivations of the person who held it. Particular stones had specific reputations and often families would travel to gain access to the most “powerful” ones.

In some towns, a municipal location like the post office, police station, or town hall would keep the mad stone, where it would could be signed out for use. In other places, the stones had names. Notably, in Kansas City, the stone was called “Mascot.”

By 1929, the Pasteur Treatment was generally accepted as effective and was available, at least by mail, from one of the Pasteur institutes to local physicians to give if someone was bitten by a dog.

Interestingly, mad stones were still in use in many places in the United States during this time. This was so much so that people were avoiding the Pasteur treatment in deference to mad stone use. Newspapers would go out of their way in articles about hydrophobia to talk about them and encourage people not to use them. I found a run of such articles in 1929:

March 7, 1929, The Tidewater Review:

August 28, 1929, The Daily American Republic, Poplar, Missouri.

The Bremen Inquirer, November 23, 1929, Bremen, Indiana

Like many folk remedies, their use seems to have died with time and age, while the stories and mystery remain.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this dive into one of the more unusual hydrophobia remedies. I’ll leave one more thing below, which is a fictional story originally published in Harper’s Weekly and then syndicated across papers by author J. Enten Cooke about mad stones. This is the clearest version I could find, and if you can’t use the link, you can go ahead and save the image and read it that way. Enjoy.

-Audrey

One response to “Mad Stones”

[…] I’ve covered cures a lot so I’m not going to deep dive into why this was in the paper. TLDR: Rabies was scary and before there was a vaccine, there was a lot of folklore about what to do if you were bit by a rabid dog. I’m sure some day I will run out of ridiculous historical cures for rabies to write about. It hasn’t happened yet, and it continues to be fascinating to me. If you want to read some other posts on this topic, you can do that here and here. […]

LikeLike