This past week, Cole Wakefield published an interesting piece on LinkedIn that addresses, among other things, the divisiveness that surrounds no kill language. It’s a interesting read and I thought that I would take the opportunity to jump from it and unpack some of the early history of the no kill movement this week.

I do now and always will believe in no kill – in it’s necessity and in it’s eventuality. The more I learn about animal welfare history and why we operate the way we do, the stronger my beliefs get. That being said, I do understand that no kill is controversial.

Everyone is welcome here, but I ask that if you show up in this space with comments, you keep them respectful and relevant to the discussion. I always do my level best to present the information in this blog as factual because my goal is to help people working in the movement understand how we got to where we are at today so that we can go forward together.

So why did the no kill movement come to be when we had been killing animals in shelters for more than 100 years?

If you’ve been hanging out with me here at Barking at the Knot, you already know that the humane movement was not at all founded on the assumption that pets would ever leave animal shelters alive. Live outcomes were a logistical impossibility in the 1860s when the movement began – there simply was not a way that the amount of animals entering shelters could have live outcomes with the resources available. (If this is new information to you, read this piece first.)

Instead the movement focused on what we felt was most beneficial to pets and people; humanely killing pets so they would not be cruelly killed on the street, and also keeping the messy business of killing away from the public eye to avoid societal corruption. The ASPCA did make an early commitment to at least attempt live outcomes. It was mentioned in a larger article covering the annual report on 1/11/1907.

In many ways, the beginnings of the no kill movement duplicated much of what happened at the beginning of the humane movement itself.

Starting in the 1960s and through the 1970s, roughly 100 years after the humane movement began, access to spay and neuter, the development of core vaccines for animals such as distemper, panleukopenia and parvo-virus, mandatory rabies vaccination legislation, education for animal welfare workers, new (marginally better) facilities, and advocacy around better education and training for shelter workers made it a possibility that at least some animals could leave the shelters alive if animal shelters were to prioritize providing live outcomes over humane death.

However, not everyone agreed then that attempting to provide live outcomes for pets in shelters should be a priority or that it was even possible. Some people saw it as a waste of resources; People problems were as prevalent in the 1970s as any other time and often took precedence over resource allocation.

Incidentally, Henry Bergh was also torn apart in the media for not including children in his original anti-cruelty work, and the same sort of criticism played out across newspapers in the early days of no kill.

Still, just as both abolitionism and Victorian gentility had the side effects of impacting the early beginnings of the humane movement by advocating for a more compassionate society, the 1970s also brought us new and different ways of thinking about societal status quos.

In this time, the civil rights movement was continuing to expand, and as the call for human rights grew, so again did the moral questioning of how society treated animals. This moral questioning was additionally influenced by counter-culture and an emerging dislike for an overstep of enforcement and authority fueled by the war in Vietnam. Most sheltering was then (and often still is) enforcement based and built on the concept of public safety.

At this point, though, it was becoming apparent that the original danger that led to the policies of mass intake of all strays to begin with (rabies) was no longer the problem that it once was. That’s not to say some animals don’t need the shelter. They do. Unfortunately, we’d already taught society at this point that the right path for every animal was intake. This is something that’s just beginning to change today.

Previous to a call for shelters themselves to do better, advocacy for pets often took the form of asking the community members to act more responsibly in articles like this one, published in 1968.

Still, small contingents of advocates across the country began to call attention to what was happening in animal shelters themselves and put the pieces together that we now had solutions to at least some of the things we had previously deemed as reasons animals could not leave shelters alive; We didn’t have solutions for everything, but people knew and recognized that we could do better than the status quo and began to call for shelters to implement the solutions that were available. Humane death for every pet was no longer acceptable.

Some shelters in this time period also began to call themselves no kill. According to Susan Houser’s excellent blog “Out the Front Door,” North Shore Animal League in New York is first credited to have used the term in it’s marketing in order to differentiate their shelter from other shelters in the area.

Some of the first references of no kill in the papers show up from organizations like Tree House Animal Foundation or Animal Protective Foundation, both in Chicago, which had national ad campaigns soliciting donations and both used no kill language in different ways – one clearly digging at the other. These ads were pulled from the Miami Herald during the mid 1970s.

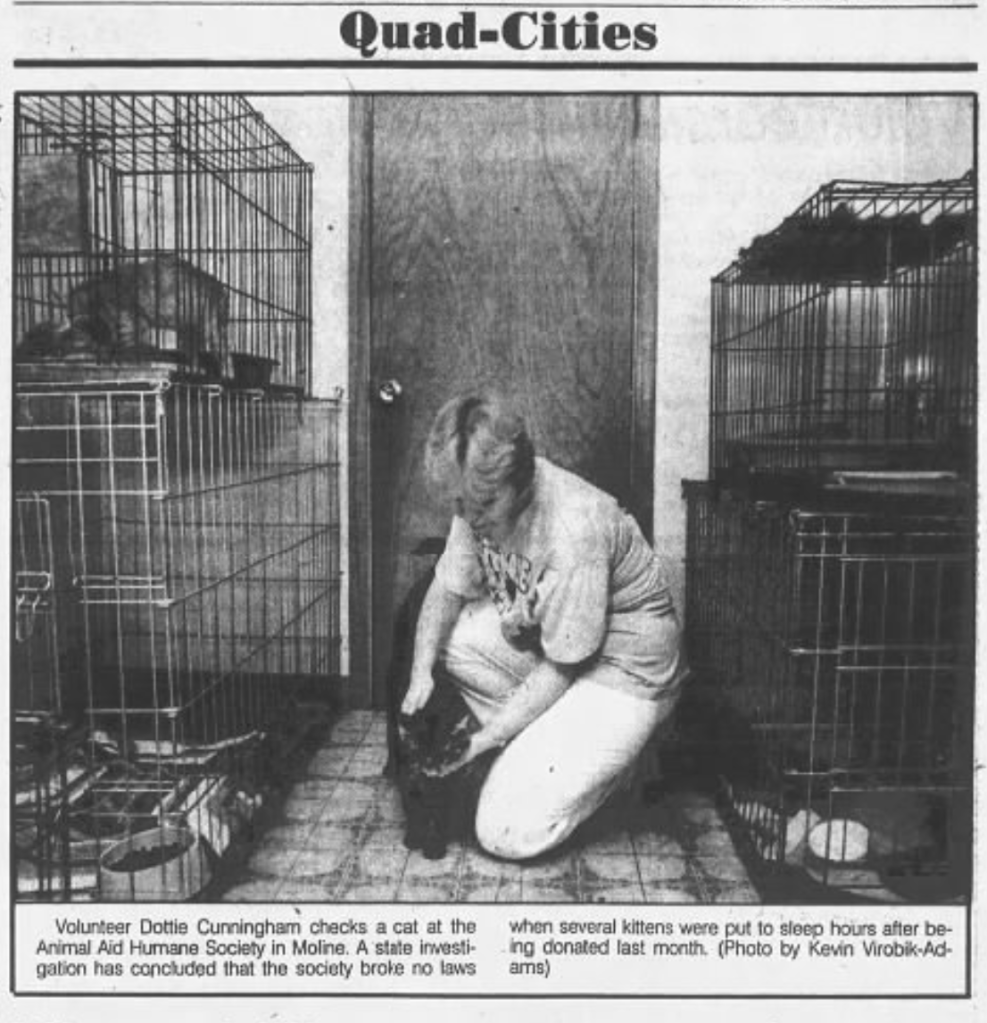

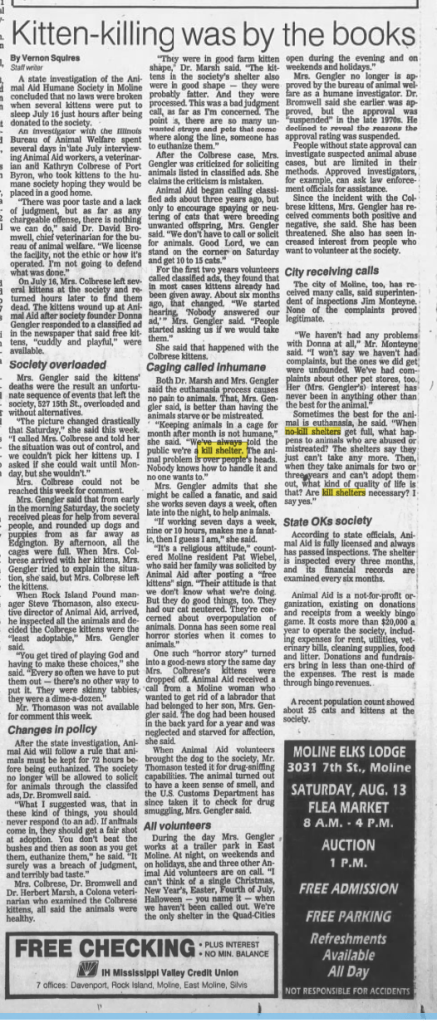

As the language began to be adopted by more advocates, shelters and rescue groups, it became much more visible in the media. This article below from a newspaper called the Argus in Rock Island, Illinois, was published on August 13, 1988. This is a great example of how early no kill played out in communities all over the country. The piece discusses the community uproar over “donated” kittens that were killed just hours after arrival to a local shelter. A state investigation found that the shelter was not operating illegally, but advocates still felt that the shelter wasn’t operating within the values they wanted for their community organization.

I don’t have any context at all about whether or not this particular shelter had what was needed to assist these kittens in this moment. It does sounds like there was someone who wanted the kittens, and that realistically they could have placed the kittens by adjusting their programming or conversing with their community.

It also sounds like they were not people who disliked animals, or were lazy, or who didn’t care about their welfare.

The piece that stuck out to me was the accusation that they were soliciting animals to enter the shelter by calling classified ads, when in fact they were calling the ads to offer spay and neuter services.

It’s truthful that in order to save lives, you need to have BOTH the mindset that you will prioritize live outcomes AND have the lifesaving programs in place to produce them. Both of those things would have been novel in this time.

The important question that this article (and this moment in history) was raising was about whether or not shelters should be held accountable at all to trying to provide live outcomes for the pets in their care.

What the no kill advocates were really asking for – albeit messily – was accountability to release as many animals alive as resources were allowed.

It followed, naturally, that if animal shelters were expected to outcome animals alive, they also needed to have the appropriate resources provided to them to do so. Time, staff, better buildings, money, etc. That became the second, very important part of no kill advocacy that is still in play today.

This is already an extremely long piece but I would also be extremely remiss if I didn’t also mention “In the Name of Mercy” by animal advocate Ed Duvin, originally published in 1989 in Animalines.

In this article, Ed Duvin dissects the existing structure of animal shelters and calls to carpet their failures. This is foundational reading, in my opinion, if you work in this movement and a fantastic snapshot of the frustrations that animal advocates were facing.

I could continue and there is much much more to discuss, but I’m going to save it for another time because really, who is reading all of this?

My goal here was simply to provide some context for the early movement and I feel as though I’ve done that.

My opinion is that no kill was extremely necessary to make visible an incredibly broken system founded on killing, and it will remain necessary until every shelter has everything they need, including the will, to consistently achieve live outcomes for every animal entering shelters that can safely and humanely have one.

-Audrey