A few months ago I started reading the paper in the New York Times archives every day for periods relevant to the humane movement. My hope was that by understanding societal events, I would gain more context around what the world looked like during the establishment of policies that influenced the humane movement, like when Henry Bergh submitted the first cruelty law for consideration, or we started employing animal control officers as municipal employees, or during the formation and attempted enforcement of the 28 hour law. I simply go to the archive, type in today’s month and day, but with a different year, and read the paper. It’s nice, actually. It beats reading the papers of today.

If you are anything like me (and in the United States) I am sure at this moment you are emotionally, physically, and politically exhausted by the state of affairs in both in our country and in our shelters, regardless of your affiliations. There are days when the “people” problems seem so big, so insurmountable, so entangled, and so all encompassing that it can be absolutely defeating to think of also showing up with enough energy, determination, emotion and passion to make a difference for people and pets. Yet we keep showing up. We do our best to understand how it’s all interrelated and try to untangle the web because we believe in the cause.

On August 19, 1866, it had been a little over four months since the New York State Legislature granted Henry Bergh the charter to officially found the ASPCA, and then, just nine days afterwards passed the nation’s first real anti-cruelty law, giving the ASPCA authority to enforce it. It was perhaps the most important moment in companion animal history.

It was also one year and four months after the end of the civil war, and also a little more than one year since the assassination of President Lincoln. The newspapers were thick with press about Reconstruction (re-building the union) and the National Union Convention had just ended. This year, the convention aimed to unify conservative republicans and democrats together in order to gain support for President Johnson’s reconstruction plan and challenge the growing influence of radical republicans.

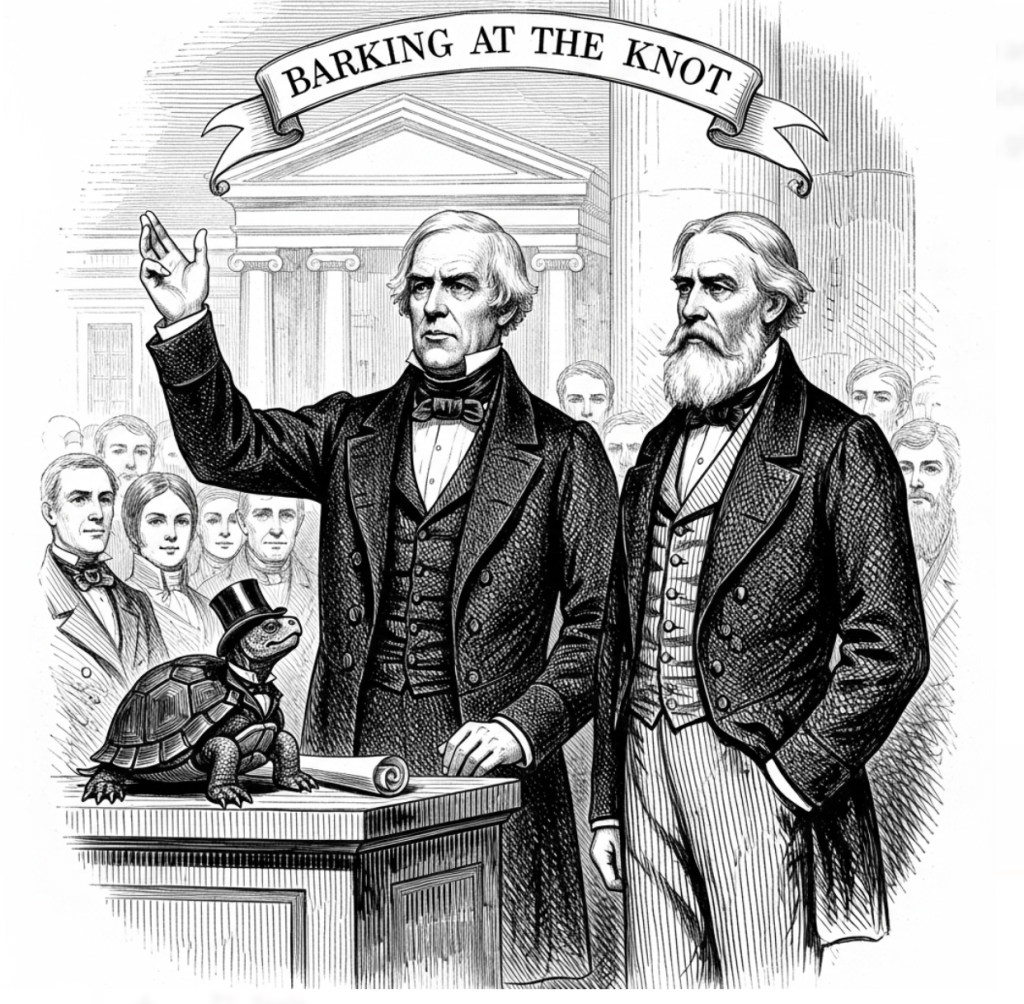

At it’s conclusion, on the steps of the venue, Andrew Johnson was to be presented with a bound copy of a summary of the convention, and slated to give a speech. This speech was published en toto on the front page of the New York Times, and in it, he reiterated his commitment to upholding the constitution. Beside him at the podium had stood Ulysses S. Grant, while Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, was notably absent. Johnson’s speech is ripe with the politics of the time, fiery, opinionated, and perhaps much more eloquent than any speech given today. Below, a segment of the speech. It feels familiar and perhaps a little depressing. The more things change, et al.

Later, in 1868, President Johnson would be the first president to be impeached by a vote of 126 to 47 for dismissing Stanton without senate consent, a violation of the Tenure of Office Act, among other things.

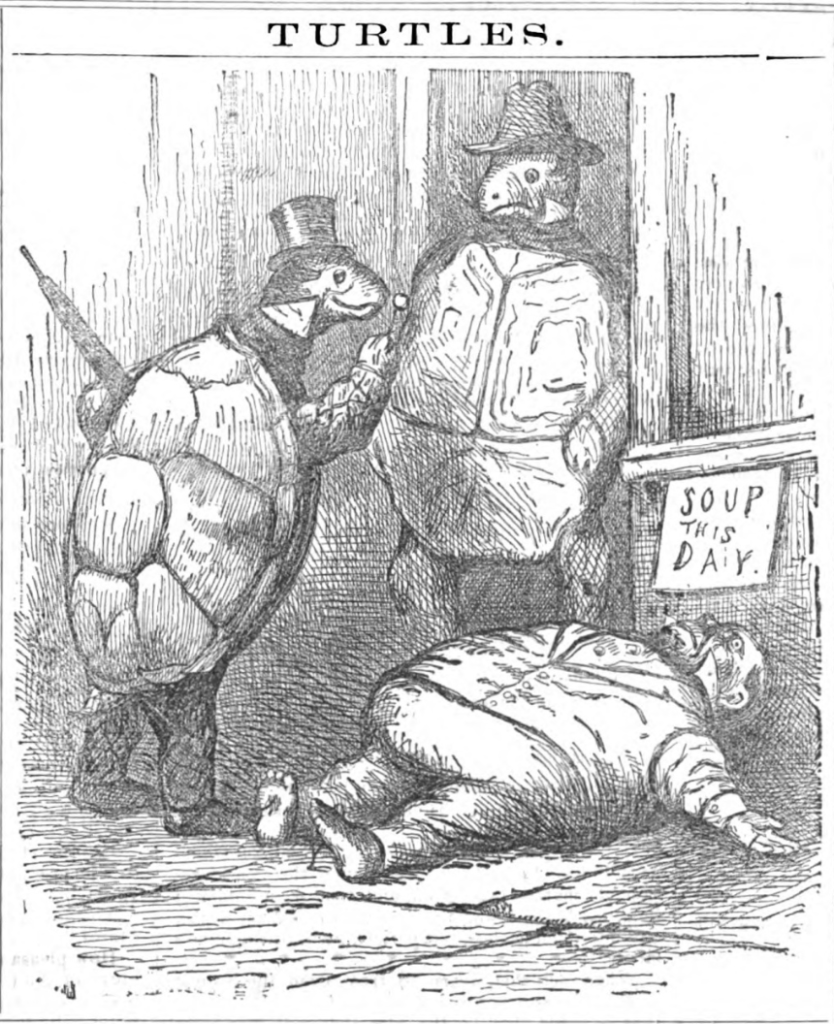

During this time, Henry Bergh was just beginning to enforce his new cruelty laws and knew that media attention was key to creating the type of societal change he desired. He also knew that because of the political climate, to garner any attention for the new law, he would have to do something extreme. It’s for this reason that one of the first acts he did to draw attention to the new law was to raid a ship carrying turtles to be used for turtle soup. At the time, turtle soup was considered a society dish. There were even turtle soup clubs, dedicated solely to it’s consumption.

The turtles themselves were captured in the Caribbean, and then cruelly transported, alive, with their fins being punctured and roped together, and the turtles shipped on their backs. Henry Bergh boarded the ship of Captain Nehemiah Calhoun, who had doubtless sailed the route and offloaded his turtles numerous times without incident, and summarily arrested him. The arrest had it’s desired affect. Across New York, the story of the maligned turtles, and subsequently, the new law, was everywhere. In the newspapers and rags, and on the lips of every society matron.

Now it’s important to note that the case Bergh was making was not about eating the turtles. It was about the cruel ways the animals were transported. He’s quoted as saying that he “Loves turtles and turtle soup.”

Unfortunately, Henry Bergh did not win his case against Captain Calhoun. It traveled all the way to the supreme court, where ultimately it was decided a turtle was not an animal, and therefore not subject to the new law. He did, however, manage to get the story in almost every paper in the country.

This story provides us with an important lesson. The more difficult things are societally, the louder and more creative we need to become to draw attention to our cause. This is not the time for throwing up our hands, even if we are exhausted. It’s the time for innovation, bravery, and for finding our turtles.

-Audrey

A couple more excepts from today’s paper: