From the beginning of the humane movement, it’s leaders worked hard to establish societal guidelines for humane ways to treat animals. Initially, Intake was a very small part of the equation. Intake into pounds and then shelters was primarily driven by public safety concerns around rabies and stray dogs, while the “rest” of the very early days of the humane movement focused heavily on treating animals well and calling attention to righting the various wrongs animals befell at the hands of humans.

Victorian gentility played a role in the very early focus on kindness in action as a primary concept. Gentility went beyond simply having a gentle character; It extended into compassion and having moral duty to other living things. This concept was often framed within religion, and advocacy in the early humane movement played heavily on the concept of people being the caretakers of God’s creation. This was a way to get people to “do the right thing” that was frequently being echoed in the churches they attended at the time, and was familiar and understandable to them. As the movement progressed, gentility was sometimes layered with the concept of the societal corruption that would assumedly occur by witnessing cruelty. Henry Bergh called this cruelism, and sometimes layered with the example of humane education being a way to raise moral children in general.

Cats initially received very little consideration or attention in the very early humane movement and were almost considered along the lines of rodents, even though today we tend to think of them as a quintessential companion pet. Cats were slowly added to shelter intake beginning around 1900 for all of the nuisance behaviors we know that cats are so great at; yowling, digging up gardens, fighting, etc. Once we had established the standard of bringing strays to a central location to be disposed of or dealt with, it made sense that cats would follow suit.

As the shelters grew and as especially cities began to have established protocols around intaking and destroying animals, they began to accept more types of animals and for a wider variety of reasons. While owners could always bring an unwanted dog or cat into a shelter, it wasn’t necessarily something that was specifically encouraged as a humane action.

By 1925, as more independent shelters were established, particularly in urban areas, things began to shift slightly and we began to see more encouragement to bring animals in for disposal as a way of being humane. In fact, most shelters would even pick them up – sometimes for a fee, sometimes not.

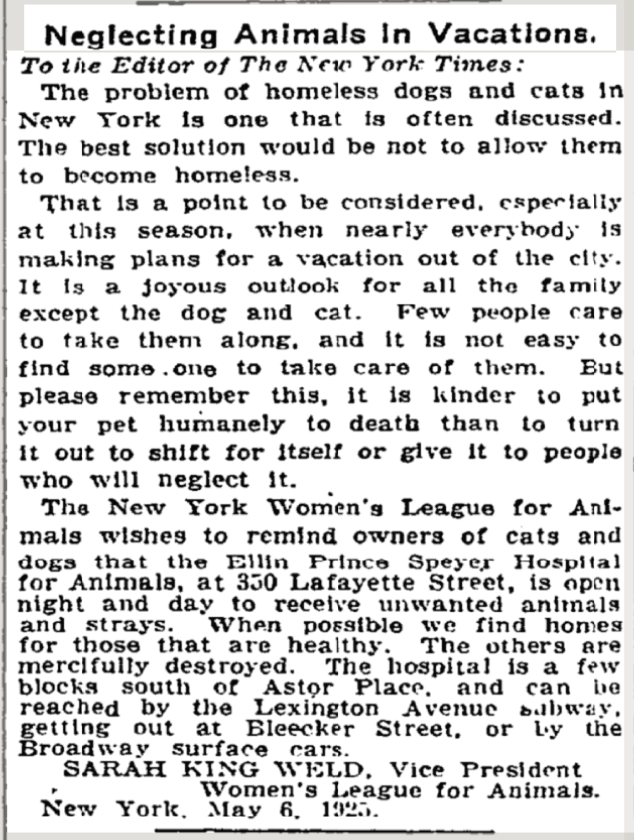

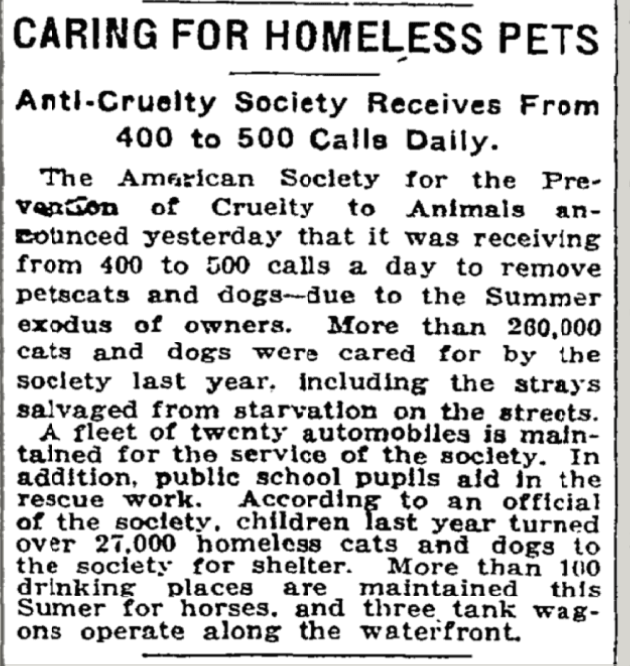

A place this was evident in the 1920s was in newspaper articles encouraging or acknowledging intake into the shelter before and during summer vacations. Two such articles are listed below. It’s noteworthy to see that there was absolutely no expectation that the shelters would attempt to live outcome the animals at all. While at this time this was still understandable due to lack of resources, it’s very interesting to acknowledge the language and expectations we were setting with the general public around what a shelter is, and what a shelter was for.

As resources did later develop and become available to increase live outcomes, and grow to a point that the majority of adoptable pets could be placed back into the community, we as an industry would be battling the societal expectations we ourselves set.

We’d then have trained our communities to believe that every animal should be accepted without question into the shelter regardless of circumstance, and that bringing them to the shelter was always the right and humane thing to do. And further, that it was OK not to have any expectation that they would be adopted, and that humanely destroying them was always a kindness.

We still are very much battling these expectations today, although the no kill movement has worked and is still working to reset these societal expectations to a place where we expect our shelters to provide a live outcome for every animal that can reasonably be placed back into community.

Soon following these articles, the great depression would affect shelter intake in new and different ways that had not been seen before, and we will be unpacking that in the next couple of posts. Comments welcome.

The articles below are from 1923 and 1925 respectively.

-Audrey