This week in Barking at the Knot, we have a guest post from fellow animal welfare worker and history lover Cole Wakefield. Cole is the Executive Director at Good Shepherd Humane Society and the Managing Advisor for Rural Humane. I’m positive you’ll enjoy this story as much as I did.

–Audrey

The Battle of Island City Homes

By Cole Wakefield

The dog problem in Galveston was once again getting out of control, and with 15% of the US rabies cases originating in Texas, those dogs posed a significant risk to public health and safety. Fortunately, Street Commissioner Tom Juneman knew precisely what to do. Juneman, following a tried-and-true method, hired some temporary dog catchers and gave orders to round up and destroy any strays in the city. Juneman must have known that the dog catcher position was not particularly beloved. He allowed them to carry pistols, not to dispatch dogs but “for protection from dog owners…”.

March 13, 1957 was a nice day, a little warm for the season, but perfect for some outdoor adventuring, and that was precisely what a pair of 14 year-old boys and their dog, Blackie, were up to. The boys lived in a housing project called Island City Homes, a collection of converted World War II worker housing that backed up to a shallow marsh. Blackie went with the boys everywhere and the posse was a regular sight on the streets of Island City Homes. Sometime around 3 pm, two of Galveston’s new dog catchers, Otis O’Callaghan and Erving Brown, confronted the youngsters and their pup. O’Callaghan discharged his firearm, with the dog catchers later claiming a shot was fired “over their heads to scare them” after the boys ran. The boys, however, insisted O’Callaghan “tried to shoot the dog” without warning, which frightened them.

Regardless of why the shot was fired, the result was an immediate and dramatic escalation. The two terrified teenagers dashed into a nearby house and emerged with a .22 rifle. One of the boys fired at O’Callaghan, and what had been a tense confrontation blossomed into the “Battle of Island City”. For nearly an hour, the two armed men chased the boys through the marsh, exchanging “sporadic shots”, some of which were ricocheting off the houses in the project. At some point during the chase, the men caught up with the boys, and a physical “struggle” ensued before the youths broke away again, shouting threats to “shoot anybody who comes near us.”

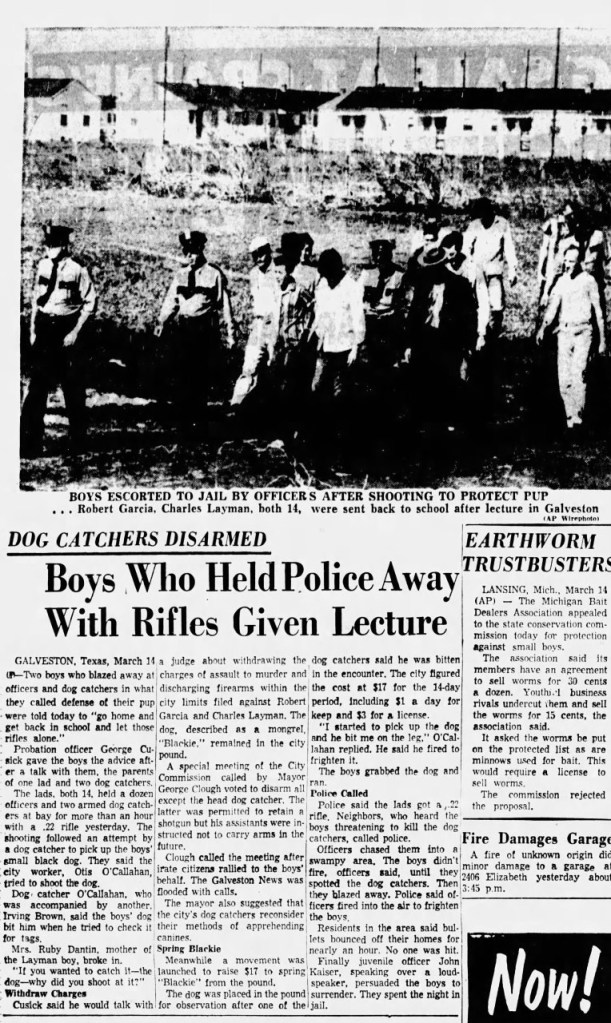

The arrival of what must have been most of the Galveston Police Department contained the situation, but it did not end. The boys, holed up in the marsh, let it be known that they had no desire to hurt police but would still love to get a shot at the dog catcher. After some back-and-forth the young teens made their only demand clear: a safe return home for Blackie. The police assured the boys that no harm would come to Blackies and the boys surrendered. They were arrested and jailed on charges of assault to murder, and discharging firearms within the city limits. Blackie, the “silent, central figure of the entire drama”, was taken to the city pound for a mandatory 14-day rabies observation, a direct consequence of O’Callaghan’s claim that the dog had bitten him. But the story does not end there.

The Battle of Island City quickly moved from the marsh to the court of public opinion. Did the citizens of Texas decry the violence and disrespect of youth? Did the city leadership rally behind their dog catchers, whose lives had been threatened? No. Not in the least. The mayor openly lamented the complaints he had previously received about the dog catchers’ methods. The public outcry was also swift, substantial, and nearly universally in favor of the boys and their quest to save Blackie. Newspapers were “flooded with calls from irate citizens”, and Mayor George Roy Clough acknowledged receiving “dozens of calls from angry citizens”. A “Save Blackie” campaign was started to cover the $17 redemption and boarding fee for Blackie, that campaign raised nearly $190 (over $2,000 today)! The public pressure led to swift and decisive action from city officials, resulting in the immediate disarming of the city’s dog catchers. A day later, the entire dog-catching team was fired, and the anti-stray dog campaign was suspended.

The boys, Charlie and Robert, had been set free after one night in jail and a slap on the wrist. Neither would face charges in connection with the incident. However, despite the community’s overwhelming efforts to save him, Blackie’s fate remained uncertain. Following the battle Charlie’s’ mother visited the pound, insisting the dog shown to her was not Blackie. The dog catchers disputed this. Later that same day, Commissioner Juneman ordered Blackie to be freed, overriding his quarantine, but pound workers could not locate him. Juneman could only speculate that Blackie was “either walking the streets of the city or was shot to death”.

The final, heartbreaking answer came the next day. On Saturday, March 16, Charlie found Blackie dead, floating underneath a bridge. Charlie’s mother reported that Blackie appeared to have been shot in the head. Although no one could prove it, most assumed Blackie’s fate was a final bit of vengeance delivered by the now former dog catchers.

The Battle of Island City, like the housing project in which it took place, has largely faded from history. Still, there are lessons to be learned. Even in 1957, when animal control was primarily concerned with public safety, with little regard for community and animal well-being, the public’s impassioned defense of Blackie and the boys illustrates the powerful emotional bond people have long shared with their pets. This profound connection challenged and ultimately reshaped the enforcement-first approach that once dominated animal control policies. The challenges facing Galveston didn’t go away that day. Dogs still roamed the streets and the deadly threat of rabies still loomed, but for a brief moment, the city’s fiercest canine defenders were its greatest heroes.

Read the original articles below: