As new humane societies were established across the country during the period following the birth of the movement, advocates explored ways to introduce the concepts of humane societies and of humane treatment of animals to their communities.

Societal beliefs around animals during this time very much centered on the thought that animals were put on earth by God for our use. Considering their emotions and care was not something most people had a strong societal expectation attached to. Within this, the conception of animals being “like us” was not a common one. Today we have much more context for understanding the similarities between ourselves and animals, including things like an understanding of our anatomies being similar and context around the ways that all living things experience emotion. These are things that we take for granted, but at the beginning of the humane movement, they were not easily understood and considered very novel.

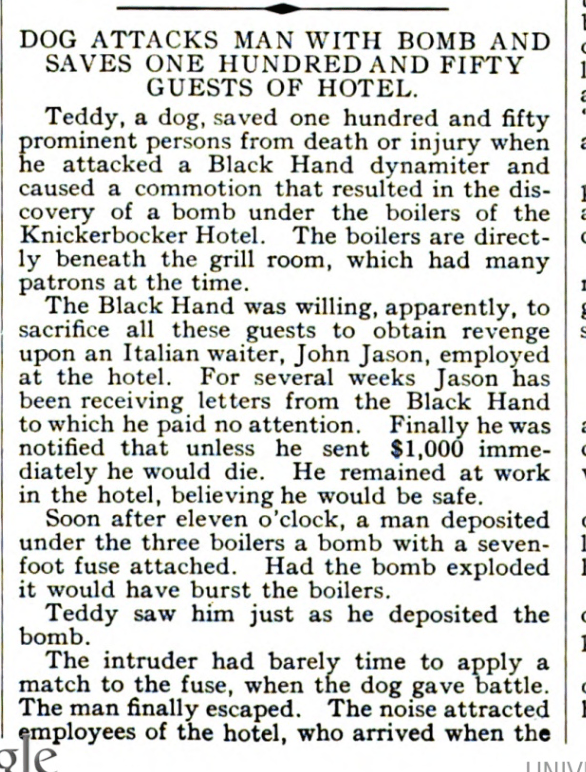

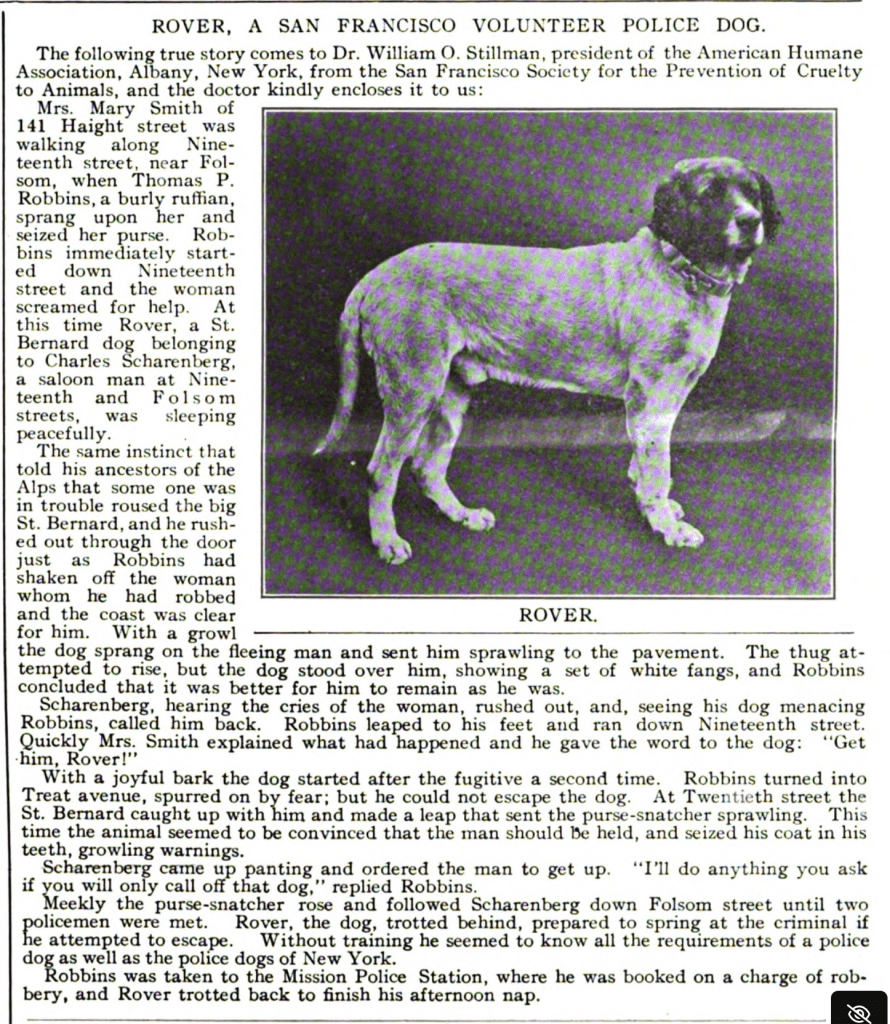

One tactic used to endear people to animals in encouragement for more humane treatment was to demonstrate their similarities to people by telling stories about them acting similarly. Particularly, that the benefits of kind treatment often resulted in demonstrations of extreme loyalty and heroism.

When you couple this with the popularity of daily periodicals, it makes sense that humane societies often used column space that was either purchased or donated to tell these stories. It bears remembering that journalistic integrity was much different then, and sensationalism was cultural and expected. As a result, these columns were generally presented as news to be considered as factual despite the actual content of the story being extremely unlikely to be true.

Below are a few examples taken from “Our Dumb Animals” in the 1908 issues that I particularly enjoyed.

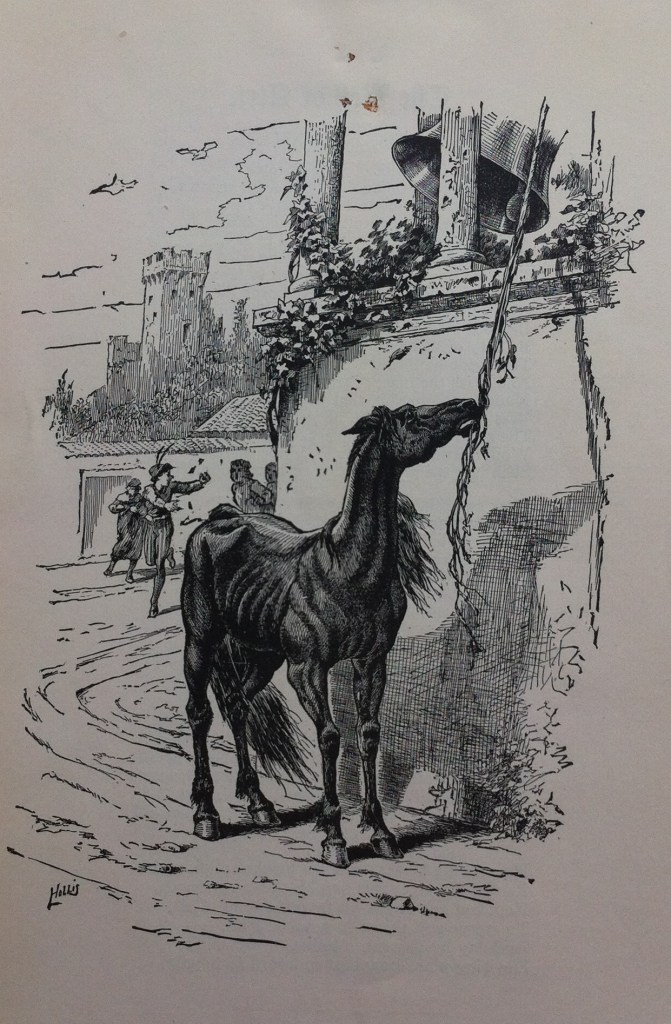

Another commonly known example of storytelling from early in the movement involves the use of a poem by Longfellow called “The Bell of Atri” to educate on humane care. The poem tells the story of a horse whose owner abandons him when he becomes too old to be useful. The horse rings the bell that had been placed in the town in case of an injustice. This horse was famously depicted in a widely circulated film made by the American Humane Education Society and published in 1920. The film was available for rent or purchase and shown to school children around the country, and the illustration that accompanied it was widely circulated and is now recognized.

Within these two types of stories we see the ways we still use storytelling today as an integral piece of how we advocate for pets and solicit support for our movement. It’s worth considering both the roots and results of the practice.

While storytelling can garner adoptions, raise funds, and showcase the personalities and unique characteristics of the animals we are working to save, we know now that it can also have detrimental effects.

One of the most difficult parts of working within the humane movement is the exposure to cases of cruelty that we experience. Sometimes, we still take it as our role to tell these stories to the public in the same way that we used to without considering whether or not we still need to use this tactic to elicit the same kind of response. Today, too much exposure to trauma may hurt our cause rather than help it by causing our communities to see shelter animals as broken. They may also anticipate a negative or depressing experience when visiting a shelter, causing them to acquire a pet in another way instead in order to avoid it.

These early stories were foundational to shifting public sentiment, as quaint and implausible as they may seem today. In reflecting on these early tools of the movement, we can better appreciate how far we’ve come, and how storytelling remains just as vital today as a tool to save lives.

-Audrey