“The close of the first century of American Independence naturally called for some extraordinary and imposing commemoration of the great event, and when it was proposed to celebrate it by an International Exhibition in which the American Republic should display to the world the triumphs it has achieved in the noble arts of peace during its first century of national existence, and in which these triumphs should be compared in friendly rivalry with those of other and older nations, there was a general and cordial response of approval from the entire nation.”

-The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exposition, 1877

Should I ever have the ability to go back in time and experience any one event, without question, I would pick the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. This event spanned from May 10 to November 10 of 1876. Intended to display for all the world the triumphs of the first 100 years of America as an independent country, the exhibition attracted 10,164,489 visitors, with more than 186,000 attending on the first day alone. The grounds, set aside and built upon specifically for the purpose of the event, spanned more than 450 acres.

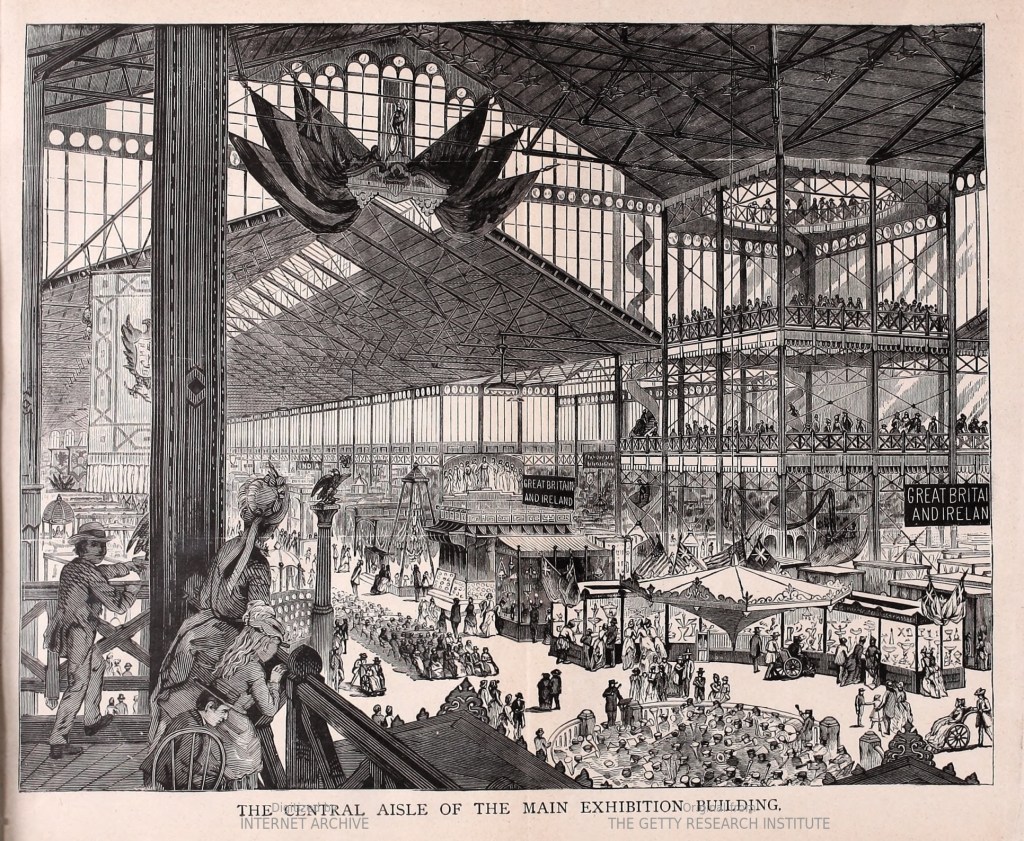

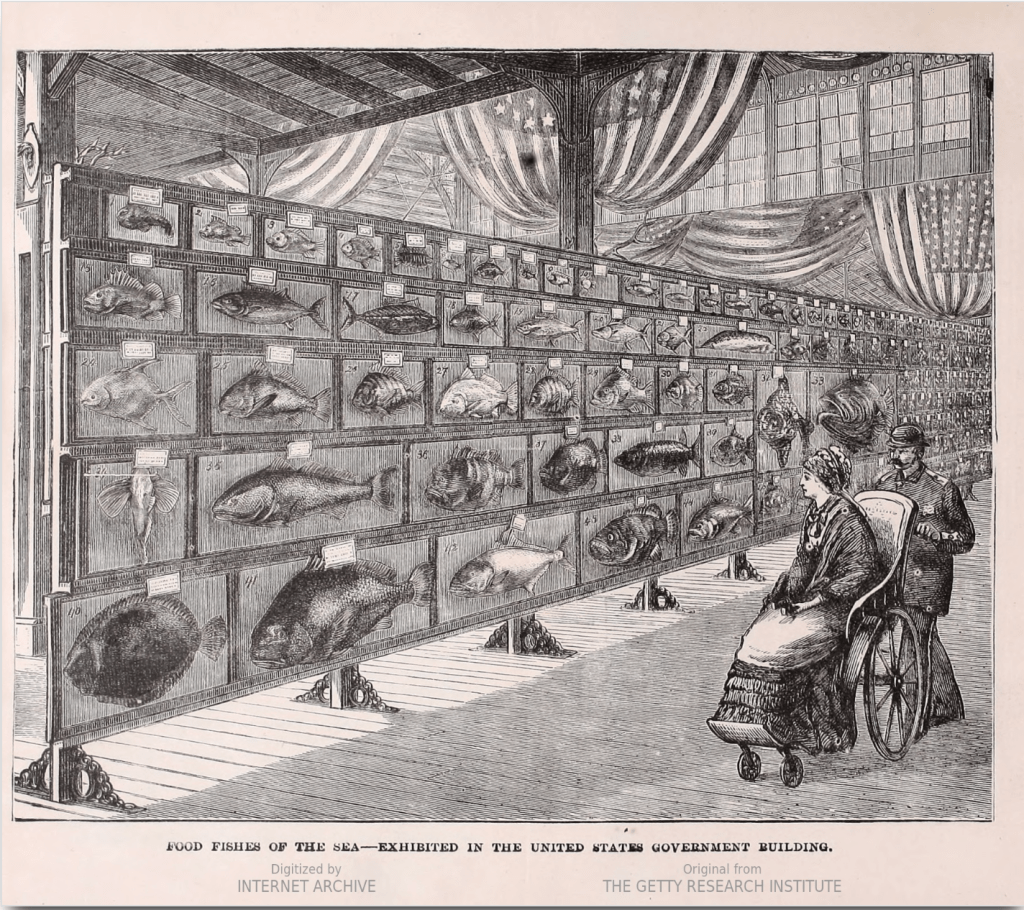

More than 200 buildings were constructed on the grounds, including special hotels made specifically to house visitors, which came from all over the world to see the exhibits. Special railroads into the event areas were created, and 27 of the 36 states also had their own “house” built in a style representative of the area’s history and architecture along a special avenue. Along with the main hall, there was an agricultural hall, a machine hall, a woman’s pavilion, a horticultural hall, and many smaller outbuildings. The Statue of Liberty’s hand and torch were on display, the rest of the statue soon to be forthcoming. There was a fire-works display described as the biggest in all of history. There was a tournament featuring fifteen knights, and a wall of every edible fish in the sea, in taxidermy. In short, it was a spectacular example of everything that makes this period in Victorian America so special.

I personally would give quite a lot to be able to see it, and I could write and write about the event itself, but of course, this is an animal welfare blog, so I will restrain myself. That being said, I can’t help but link some ephemera about the Exposition at the bottom of this page. If you like this period of time, you will like to learn about this event (and maybe check Ebay for some relics) animal welfare history aside.

Of course, 1876 was just ten years after Henry Bergh founded the ASPCA and enacted our first cruelty laws, and there was much for he and other humane leaders to share with the public about the movement at the Exposition.

Of particular note is the vigor with which George Angell threw himself into the event.

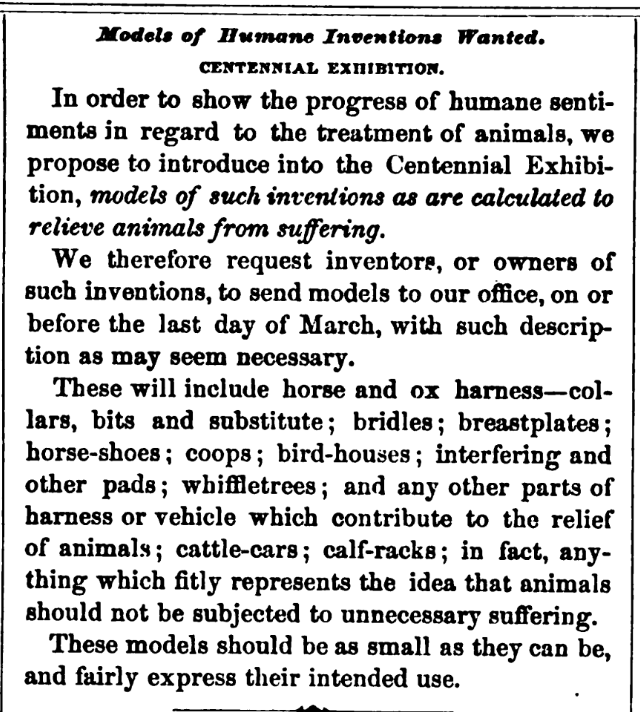

In the February, 1876 issue of “Our Dumb Animals,” the monthly periodical of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, we see an enthusiastic ad requesting humane inventions for display in Philadelphia. The Massachusetts SPCA was to be in the educational exhibit in the main building, number 77.

In line with the event itself, the request was specific to showing progress toward a more humane society.

And submit, they did! The final round up of inventions displayed was pretty remarkable. It’s notable to mention that George Angell was heavily involved in the movement to transport cattle more humanely from the west to the northeast after the 28 hour law was enacted, but rarely enforced. At some point I’ll write about that. Meanwhile, you can see that reflected here in the humane livestock cars submitted as inventions.

Ads ran in “Our Dumb Animals” throughout the duration of the event, encouraging people to see the exhibit. Of note is where the exhibit itself was placed. In line with Angell’s belief that the best way to affect societal change is to educate the public, his exhibit was in the educational building. Along with the inventions, he had a seating area and a collection of pamphlets, humane children’s books, and issues of both “Our Dumb Animals” and “The Journal of Zoophily.”

Henry Bergh also exhibited at the Centennial, but his exhibits were in line with his own beliefs that enforcement was the best way to gain compliance.

I was able to obtain a copy of an article about Bergh’s exhibit by buying an engraving from an issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 13, 1877, on Ebay. A photocopy of the article was included, and I’ll paste it below even though the quality is not that great. It was NOT easy to come by and I’m pretty excited to have it. The article describes the exhibit as such:

“The curious and remarkable display made by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Henry Berg, (sic) President, at the Centennial Exhibition, excited great interest among the throngs of visitors, especially foreigners. The space secured at the extreme east end of the north side of the main building was prominently indicated by a handsomely painted banner, 25 feet ling by 20 feet wide, which was suspended by the iron rafters of the roof. Upon the banner appeared the names of all the states and territories which have laws for the prevention of cruelty to animals on their statute-books, together with the names of the founders and parent societies in each State. There was also displayed an elegant silk banner, which was presented to the society by a number of ladies at the annual meeting held in 1876. The entire wall space of the section assigned to the society was covered with photographs taken at the time of arrests, and illustrating particular cases of cruelty. Among them is a large, stuffed bull dog which was captured at Karl’s Park, Morrisania, during a fight. The dog’s head, neck and body, which had been badly cut, presented terrible evidence of the brutality of dog fighters. There were aso a number of stuffed game-cocks, with steel spurs, taken at Mains, and several pigeons found wounded after pigeon matches. In two glass cases are some hundreds of weapons, such as clubs, car hooks, stones, rungs, hammers, hatchets, etc.”

Following this description is a long list of items exhibited, each gorier than the next. The article closes by noting that 20,000 pamphlets were distributed to visitors.

Below is a photograph of the article. I will scan it in properly and add it to the book list as well, since it is difficult to find.

While I could find no actual photographs of either exhibit, that doesn’t mean they aren’t out there, somewhere. There are several notable collections of stereoscopic view photography from the event, and they are very interesting to see. I frequently hunt on Ebay and in antique shops, just to see if one turns up.

Our movement’s presence at the Centennial Exposition is yet another fantastic illustration of how we changed the hearts and minds of a society to be more compassionate toward animals. It’s so interesting to me to see the differences in approach taken by Henry Bergh and George Angell for influencing the public at this event. Ten million people visited the Centennial Exposition from all over the world. For many of them, this exhibit was the first time they had ever encountered anything relating to the Humane Movement. Given it’s contents, the exhibit must have seemed quite radical and I imagine the conversations it evoked must have been extremely interesting. I like to think about what the current version of this might look like. There are still new and radical ideas emerging as part of the humane movement, and I assume there will continue to be for some time, as we still have a long way to go.

– Audrey

Links

Sheet music for the Grand March conducted at the Exposition

An illustrated guide: The Centennial exposition, described and illustrated, being a concise and graphic description of this grand enterprise, commemorative of the first centennary [!] of American independence … By J.S. Ingram