Go back a bit before municipal dog catchers, which came to be in roughly 1870 in the United States, and you’ll find the Enlightenment period.

The Enlightenment, which lasted from about 1760 to roughly 1813, was a period of time that valued reason and science over blind faith. It concerned itself with social ideas and political ideals, and it examined the ways that humans themselves operated within these ideals. Examples might include ideals like fundamental human rights, the separation of church and state, and the concept of individualism. Overarchingly, the goal of those enlightened thinkers was to advance society to be the best version of themselves.

This period and it’s way of thinking was still a heavy influence on culture in 1870s, particularly in urbanizing areas. It had influenced what we know to be the transition from court etiquette to common etiquette, it drove the idea that people should be concerned with elevating themselves above corruption, and it certainly had paved the way for the abolishment of slavery and with that, the recently concluded but still very present Civil war.

Enlightened thinking evolved, particularly in urban areas, to the concept of what makes a decent person in society. We very much see the idea of what it means to be a gentleman, or a lady, front in center in daily life. Victorian gentility, and the extremely Victorian nature of worrying about one’s appearance, manners, perception to the public, cleanliness, godliness and soul, abounds. Even in poorer areas and lower classes, the perception of one’s character is of the utmost importance.

In urban cities where rapidly growing populations of varying ethnicities and cultures were coming together, another version of this sort of gentility looked like creating a combined, accepted way of living. There was a blending of customs, traditions, mannerisms and classes to create a modern day city. In wealthy areas and in poor areas, people were, in fact, establishing the morals and ethics of a whole new society. Social order abounded and proprietary was the ruler of the day.

So what of dogs within this?

Dogs themselves also had their classes, with the “purebred” dogs of the wealthy living a whole different life than the so-called curs, mongrels and yellow dogs living in the streets. This new urbane society had established class all over again without royalty, and they certainly recognized class structure even within dogs. Some thought, for example, that all street dogs carried hydrophobia (rabies) inherently, while well bred dogs didn’t carry it at all; And when the Westminster Kennel Club’s first competitive dog show happened in 1877 in New York City, featuring 1200 pure-bred dogs of all shapes and sizes and Henry Bergh himself as a speaker, it’s not without irony to note that simultaneously a wire cage of mutts was being drowned in the east river for being stray.

In New York City, the roaming packs of nuisance dogs in the streets and a terrifying fear of hydrophobia had long led to goverment provided bounties in the summer months of 50 cents a nose for any stray brought to the central pound. It’s here we get the phrase “Dog Days of Summer.”

Even there, dogs would be sorted and purebred dogs set aside for a chance at reclamation while strays were almost immediately killed.

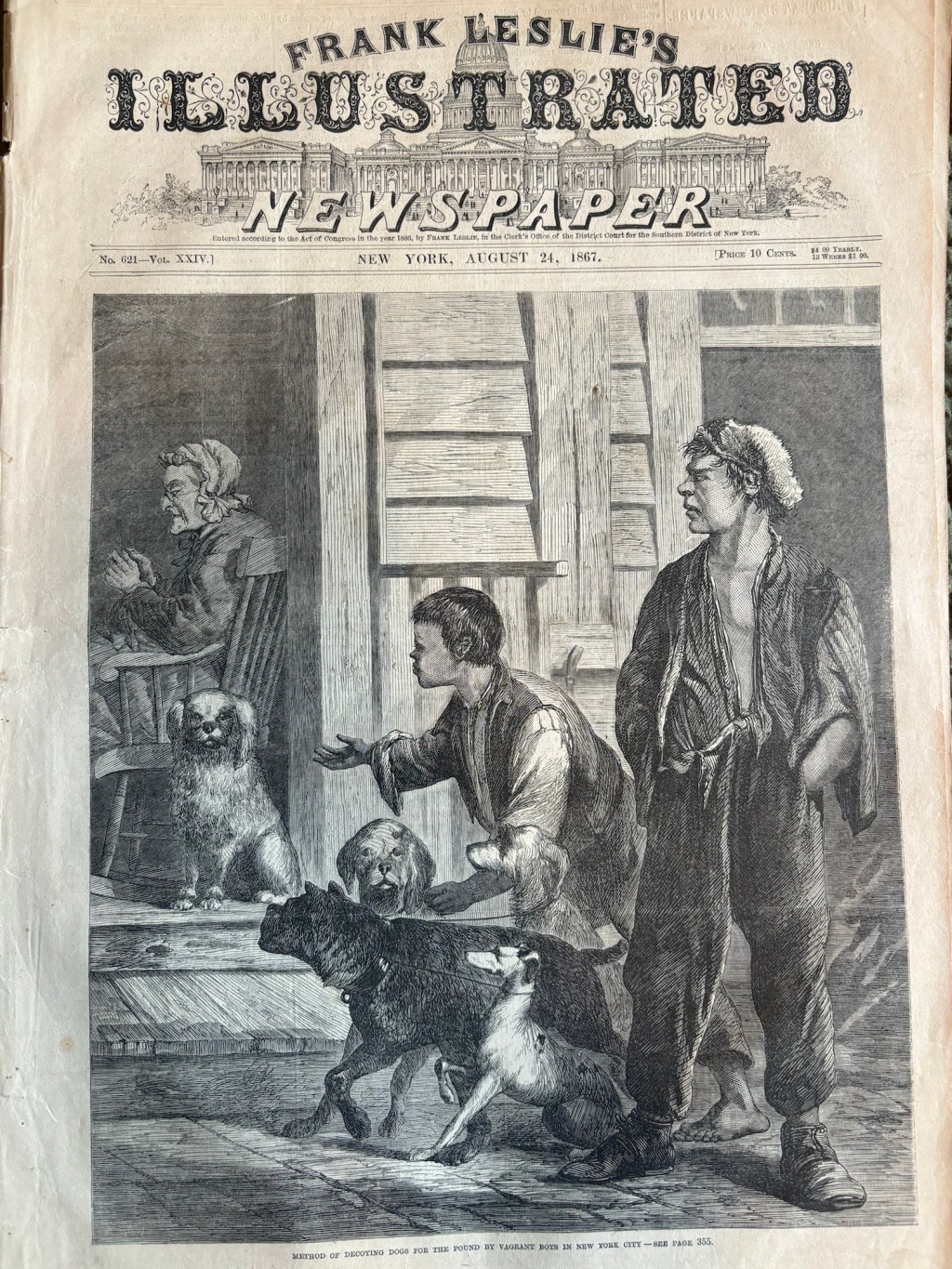

Alas, these dog bounties promised good money for young children, who commonly worked all manner of job in the streets. Children were also expected, particularly in neighborhoods full of cramped tenement apartments, to stay out of doors and out from underfoot during the day. And so primarily young boys, desperate for money either for their families or simply for a sweet, resorted to catching dogs, owned or unowned, and bringing them to the local shady middleman who would turn them in to the impound for pay. The children had all manner of tactics for catching the dogs. I’ve read described having a favorite dog that would chase out others to be captured. I’ve read about baiting dogs, about snaring them with wire, and about the blackmail some children would conduct on the wealthy after stealing beloved pets. The profits could be substantial, even for a young boy.

Around this same time a movement began within New York society around the corruption of young boys. As the city continued to intensify, grow and organize, the things that children did to gain finances or entertain themselves grew more concerning to the masses. Along with stray dog catching, young children on the street could witness and participate in other debauchery as well. Watching meat animals be killed in the livestock pens throughout the city, for example, or killing wounded pigeons from pigeon shooting matches. Or watching the strays be drowned in the river, or the carriage horses be beaten in the street. All of this served as a gristly form of entertainment and influenced their perception of animals and of the ways it was acceptable to treat both them and each other. And while Victorians were known for their fascination of the macabre, they also worried about what would happen to the souls of these boys for witnessing and participating in this violence. Anti-vice societies took the issue up as a cause.

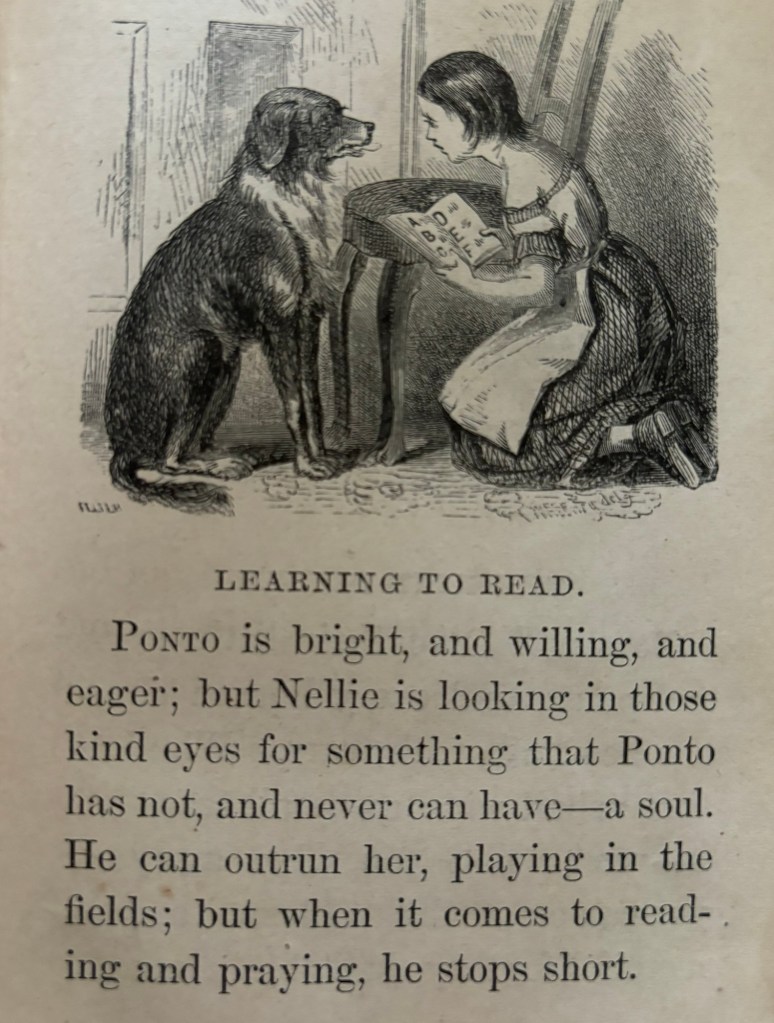

With the foundation of the humane movement came campaigns to teach children (and adults) compassion for animals. Kind depictions of animals appeared in newspapers, children’s books, pamphlets and religious materials. These depictions encouraged everyone to recognize that although we needed animals to work and for food, the appropriate thing to do was to never cause them undue suffering.

Along with this humane education of course came the argument that the humane movement could not succeed if boys were still capturing strays in the streets. The city took several ineffective measures at first, cutting the bounty from fifty cents to twenty five, and no longer allowing children to bring the dogs in directly. These measures had limited success, since children couldn’t drive the dogs to the pound anyway and had long relied on dog brokers to provide their reward. With the pay cut the reward was less but never nothing, and it wasn’t enough to dissuade boys from the habit.

Eventually, though, in 1870 public pressure due to not only the potential corruption of children, but multiple issues involving strays, won out and the city allowed the ASPCA to formally hire “dog officers” to round up the strays. In addition to removing children from the process, these officers were being taught to handle the dogs more humanely and appeared as professionals, with uniforms and badges. Although many of the original ASPCA dog catchers were simply the corrupt dog brokers now paid for a salary, eventually professionalism prevailed and this last step of removing stray management from the hands of citizens was complete. It also completed the circle of removing killing from the public eye, which led later to a lack of transparency within the industry around the numbers of dogs and cats dying in shelters. Alas, however, that’s a story for a different day.

-Audrey