I recently acquired the 18th annual report of The State Board of Health of Massachusetts, circa 1887, at an estate sale and of course, I quickly looked up hydrophobia (rabies). As one does.

My excitement stemmed from the fact that this was a pivotal time in history for the development of regulations around rabies and its impact on pets. Here’s what I found:

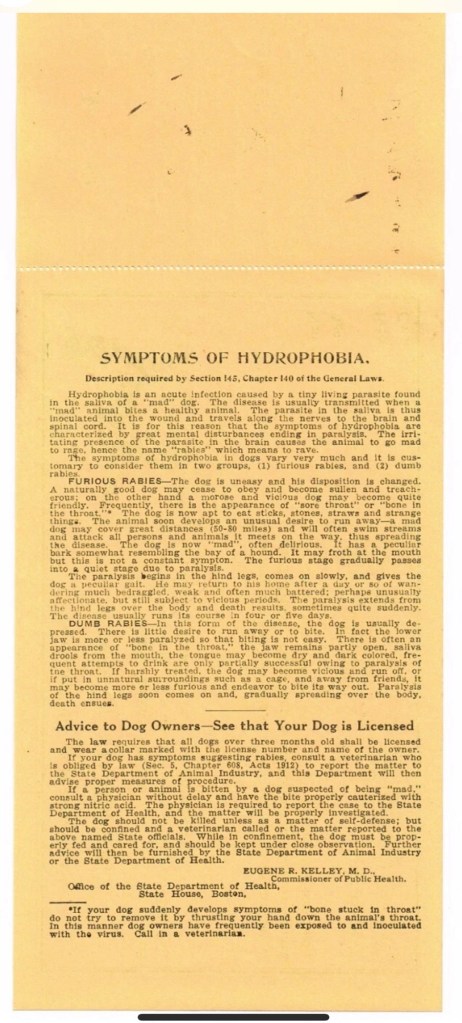

Included in this annual report was a newly adopted state ordinance mandating that those municipalities issuing dog licenses within the state of Massachusetts describe hydrophobia on the license itself, and additionally make descriptions of the disease available to those municipalities issuing licenses.

I was able to find an example of a license that did contain the description of hydrophobia from 1923. It seems it took a while to go from ordinance acceptance to implementation, which was common in that time (and common today still.)

In 1887 State health departments were becoming more formalized and tasked with not only management of hydrophobia, which was low on their list of priorities due to its rare occurrence, but with the much larger task of “sanitizing” and protecting their communities from all types of disease.

The adoption of germ theory gave solidity and direction to their work, since there was now a direct link (and therefore directly identifiable solutions) between disease causation and the populations they effected. Due to this, health departments were rapidly expanding.

So also at this time was a developing understanding (and skepticism, to be fair) of what “germ” hydrophobia was caused by and what role the health department had in managing it. This was especially relevant because there was a new “treatment” for people who had been bitten by a “mad animal” that was becoming commonly accepted… although the effectiveness was still being hotly debated, particularly in New York City. However, with rabies being entirely fatal without it, those bitten tended to err on the side of caution. This treatment, a post bite exposure vaccination, or the “Pasteur Treatment” as it was colloquially known, had been developed by Louis Pasteur in Paris.

Still, 1887 was almost entirely before access to the Pasteur treatment for people in the United States; Those wealthy enough and with means to travel could access the treatment in Paris at the Pasteur Institute if they were timely enough to arrive in the window between bite and onset of symptoms. Within the US, the soon to be failed American Pasteur institute was technically operational in New York City during 1887, although riddled with funding and production issues, rendering it entirely unreliable. The institute was thought to only fully treat around a dozen people during the entirety of it’s operation. The much more successful New York Pasteur Institute would open in November of 1888, providing the first real access to the Pasteur treatment in the United States. Much later, in 1914 in New York City, the health department would take over as the primary provider of this care and this model would be quickly replicated across the country with vaccine kits being mailed to the most remote physicians.

It is within this frame in 1887 that health departments were refining their involvement in the management of the dog population in relationship to hydrophobia within their communities. Health Departments were dovetailing with the still newly established animal rights movement, the pre-existing and often still citizen led (and sometimes government incentivized) norm of culling stray dogs from the streets, and, in larger cities, the advent of a formalized (and often corrupt) animal control. There were a lot of players in the arena of stray dog management.

The primary concern of health departments was then and remains still removal of disease from community in the name of public safety. Since the primary source of of hydrophobia in people, and especially in children, was stray dogs, their primary goal in relationship to pet ownership was that stray dogs be removed from the streets. To this end, they sometimes created the ordinances that required licenses and sometimes supported them with supplemental ordinances like the one shown above. But why?

Well, the intersection of dog licenses and rabies is something that is misunderstood in animal services, with many municipalities and animal services agencies still enforcing licensing above many other more important issues, operating under the impression that the reason for a dog license is to prove a dog is vaccinated and therefore to protect the community from rabies; However, the original purpose of the dog license was to prove a dog is owned, so that they would not be removed.

As laws like leash laws and mandatory muzzling were created, particularly in cities, to protect the public from roaming dogs that could potentially bite, licensing followed to allow pet owners a path to reclamation, should their dog be confiscated. So, while it’s true that stray dogs were primarily causal of rabies in people, it’s incorrect that licenses originally developed as a way to manage rabies. They were simply a means to determine an owned dog from a stray dog.

Dogs themselves were not vaccinated commonly until much later in time. Although there was knowledge in the 1890s that the vaccine was effective in dogs and several expensive owned dogs had even been vaccinated for one reason or another, It wasn’t until the 1940’s that we see rabies vaccines given to dogs as a social norm. In 1954 the CDC and national health department launched a campaign to encourage vaccines, and it was not until the 1970s that all states had a vaccination requirement.

Licensing also generated funding, since dog licenses came with a cost, and it was often solely these monies that allowed animal control agencies to continue their work. This model of funding as a sole source of income for animal services agencies is part of the reason that licenses still exist today, even though dog licensing is no longer the best way to prove ownership of a pet.

Today, animal services providers should ask themselves whether mandatory dog licenses are serving any purpose at all within their communities aside from raising funds. Proof of ownership is much better identified through microchipping, and while rabies prevention was never the intention of dog licenses, no one can argue is much better served through access to free vaccines than through a piece of paper. Both of these things are easily provided through community clinics, and resources should be directed thusly. Do we require a vaccine to get a dog license? Yes…mostly. Do we have other technology now that can track this information? Yes, definitely.

As far as the funding piece goes, pets are recognized now as an integral part of any community. Municipalities have a responsibility to direct appropriate funding to the care and protection of animals, and that includes sourcing funding the most progressive of programs instead of leaning on outdated funding methods to support programming that doesn’t serve anyone well.

-Audrey